Song Ling rides the New Wave of Chinese art

Living between Hangzhou and Melbourne, the Lunar Lantern artist's work is politically charged with flairs of Magritte

Over Lunar New Year, Sydney’s harbour is dotted with giant luminous lanterns shaped like the animals of the Chinese zodiac—from a towering ram made of mahjong tiles to twelve scantily-clad dancing rats. The centrepiece is an eight-metre tall dog sitting stoicly beneath the Opera House sails. The Lunar Lantern, a contemporary interpretation of a centuries-old tradition, was commissioned by the City of Sydney and created by Melbourne-via-Hangzhou artist Song Ling.

Giant Labrador-shaped sculptures are a new venture for the trained ink painter and proponent of China’s New Wave (ba wu shing tao) of the 1980s. Ling graduated in 1984 from the China Academy of Art, majoring in traditional ink painting techniques yet never applying them to traditional paintings,

In the late ‘70s, China introduced the Open Door Policy, an economic reform that opened the country up to the rest of the world for the first time. For the artists of the New Wave, it was the first time they were able to witness art from the Western world (for Ling, Salvador Dalí and René Magritte resonated the most), learn foreign techniques, and digest the concepts behind these works.

Ling has spent the last thirty years living in Melbourne, raising a family and practising his art while travelling back and forth between Australia and his home in the lakeside Hangzhou in China’s Zhejiang province. This Lunar Lantern commission allowed Ling to realise his traditionally black-and-white ink wash techniques in vibrant sculptural form.

How do you approach painting something that’s large and right next to the Opera House, compared to painting ink on a canvas?

The City contacted me when I was in China for this work. It’s quite different to my own paintings, where I use black and white, colours closer to the environment in China—concrete buildings and jungles. Animals are often kept in concrete buildings and it’s sad to see that. With the dog, I designed it with a few pencil sketches, picked colour samples, designed its costume, and painted watercolours over it.

You’ve said that your colour palette is drawn from Chinese folk art and embroidery?

Currently, a lot of my own work is black and white. For Lunar New Year I preferred a colourful, happier look. The dog is influenced from Chinese folk art like paper cutting and embroidery. The blue, green and pink is from Chinese art, with orange brush strokes imitating watercolour patterns.

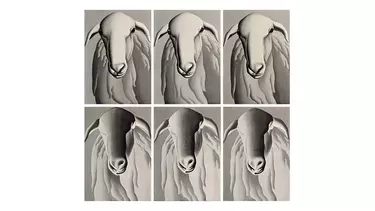

Your early work is in black-and-white ink wash, and it’s quite dark. One of your works is a painting of an expressionless sheep.

It’s called Meaningless Choice No. 1—there are actually six parts to that work, influenced by Andy Warhol’s repeated images. I was imagining the Chinese people of the early ‘80s and using sheep to symbolise them. There was a lot of political pressure at the time, very different to now. They were struggling but didn’t feel like they had enough power. They were like sheep, with someone to look after them. They didn’t have any freedom. We didn’t have the freedom to follow our own path, and the sheep show that in their faces—hopelessness (wu nai).

My art today shows Chinese people as they are now, like animals fighting. The Chinese have a lot of ambition (kan lan) in the way they do business. The big fish eat the small fish. They’re fighting each other and it’s not like the ‘80s anymore.

What defined the New Wave movement in China?

We didn’t mean to make it a movement, but when we look back we see it as one. We were young then, only twentysomething. The work we were doing then was different to what mainstream Chinese artists made. Every city in China had these New Wave artists, all rethinking how we could express ourselves through art. Chinese art was always about propaganda and doing things for the government. We thought we could do something for ourselves, say something with our own emotions.

We thought we could do something for ourselves, say something with our own emotions.

You’ve been in Melbourne for three decades now. Do you consider yourself a Chinese artist, or a Chinese-Australian artist?

When I graduated from school I never did traditional Chinese art. I’m a contemporary artist. I still use ink but it doesn’t really look like a traditional Chinese painting.

Your Australian work is more colourful, and yet your Chinese art is darker?

During my early years in Australia, I was with my son a lot, taking him to school, to childcare. My wife works in a bank, so she’s very busy. Because I was an artist, I stayed home to look after my son—that was my job. My work was influenced by life with my son. Here, it’s quiet and stable.

Back in China, life is different. It’s challenging over there. You have a lot of potential, but you don’t know what’s going to happen next week. I don’t mean it’s dark—the black and white work is more suited to what I think about art at the moment. You have more chance for expression, and it makes you think more.