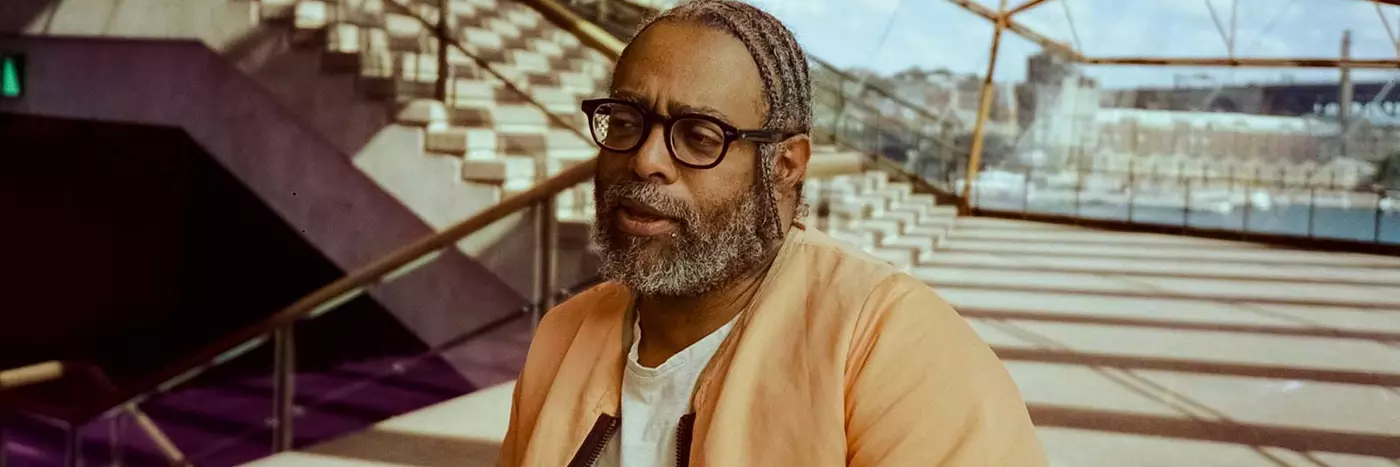

For Arthur Jafa, Black art is the heart of America

Set to Kanye West's 'Ultralight Beam', Arthur Jafa's acclaimed seven-minute film Love is the Message, the Message is Death, essays and celebrates a tumultuous century of African-American history and culture, in the process invoking everyone from Martin Luther King, Jr. and John Coltrane, to Nina Simone, Beyoncé, Michael Jordan, and The Notorious B.I.G.

Jafa first rose to prominence as the cinematographer on Julie Dash’s groundbreaking Daughters of the Dust (1991). He has since shot films for Spike Lee and Stanley Kubrick and most recently worked as a cinematographer with Solange and Jay-Z. His work has been collected by museums worldwide including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles and The Smithsonian.

At Vivid LIVE 2019, the film screened alongside a conversation with the filmmaker. The Opera House's visual art curator Sarah Rees spoke to Jafa in Sydney – watch a short clip from the interview and read the full transcript below.

Sarah Rees’ role as Sydney Opera House’s Curator, Contemporary Art is enabled by Cathy and Andrew Cameron AM.

Most Australians have an idea of the American South that is constructed from a variety of media sources: film, literature, music – often horrific historical accounts and sometimes romanticised stories. Can you tell us a little about what the reality was like for you growing up in Tupelo, Mississippi?

It is pretty romantic and pretty horrific at the same time. I had a running joke for years, that if I ever do my memoirs it's going to be called ‘Dark and Lovely’, which is a bit of a joke because it's a black hair care product. It’s a very particular place to grow up in and it's certainly informed my worldview. I mean, it sort of shaped me.

I grew up there in a very particular moment in history, the seventies. I moved from Tupelo, Mississippi – the home of Elvis Presley where I was born – when I was six years old to Clarksdale, which is oftentimes referred to as the capital of the Mississippi Delta. It's a region that's known for some of the more horrific murders.

But coming out of the sixties into the seventies was a period where there was a lot of optimism, optimism about changes in society at large and I experienced a lot of that. My first year of elementary school I was in the first integrated class that they had in the history of Tupelo, Mississippi. Prior to my first year the kindergarten was segregated. There was a Black high school and a White high school.

What kinds of creative influence did that place have on you?

Tulepo is also like ground zero in terms of Black America musical culture. Being ground zero for Black America music culture means it's ground zero for American music culture. And in the 20th century that means it’s ground zero for American culture, period. That fact is so indisputable that Dave Hickey said that pop music – which is essentially Black music – is a dominant culture form of the 20th century.

There’s an incredible amount of diversity that was shaped under the umbrella of subsets of Black music. That includes everything from jazz to blues to rock and rock to hip-hop to techno. It's sort of unending.

You know I think about the only other thing that you could argue had a bigger influence on culture is maybe cinema. But at the end of the day most people would say pop music is the dominant form just because it evolved a lot more violently.

So how does film and cinema continue to influence your work? Your early career as a cinematographer involved shooting for some high profile directors and accolades… You won the Best Cinematography award at Sundance in 1991 for your work on Julie Dash’s Daughter of the Dust, but what was it that made you prioritise your visual art practice?

Well you know it's funny. Somebody just recently asked something like, “So why did you choose art over cinema?” And I just started laughing. I was like, I didn't choose art over cinema. Art sort of chose me, you know.

I was studying architecture at Howard University, but if someone had asked me what I was interested in doing, I probably would have responded something like of Kind of Blue, or Electric Ladyland or Concrete Jungle or I Want You or any great Black album – I wanted to work out what they would look like if they were houses, you know?

Using that sense of difference from within Black music to see if it was possible to create a Black architecture, something that seemed specifically Black.

I actually became somewhat dismayed that it was going to be impossible not to imagine it but it was going to impossible to make a living doing it. People I knew didn't own homes or they certainly weren't in the position to commission me as an architect to create some experimental architecture thing. So because of that, when I ended up in the film department at Howard it wasn't a very complicated conceptual shift for me to make. Even though I hadn't really entertained the idea of Black cinema per se I got it straight off you know?

While I was there I stumbled into one of the epicentres of what's been called UCLA Rebellion, a group of filmmakers who operated out of UCLA in the mid-seventies. Charles Burnett, Haile Gerima, Larry Clark, Ben Caldwell, Julie Dash. That was a group explosion, arriving at idiomatic, Black modalities in filmmaking. They were trying to create a real Black cinema.

I went to LA to work with Charles for about four months on My Brother's Wedding. I met Julie Dash on that and ended up shooting Daughters of the Dust for her, which was kind of successful in the early ‘90s. From there I was second unit director of photography on Malcolm X which was a rally big leap for me. Spike Lee saw Daughters of the Dust with Ernest Dickerson who was a cinematographer and they invited me to come work with them. So it was a real learning experience. And after Malcolm X I ended up shooting Crooklyn for Spike.

I was staring feel like I had gone down a course that I hadn't intended to go down. I wasn’t trying to be a cinematographer, I just assumed I would be shooting my own films. But up until then it was the most lucrative thing I knew how to do. And it was exciting.

Then at a certain point I became increasingly disenchanted with a lot of aspects of what I was doing. I didn't feel like I was operating at my fullest capacity. The methodologies and protocols in place seemed insufficient to get at some of the kinds of things that I was interested in getting at.

There’s an inherent, undeniable power of our music. And not just that it’s powerful but it’s something that we created, that we own. And owning things is a big deal for us because we were owned.

And what kinds of things were they?

You know a lot of times people they think about art and they think about the product. But they don't really think about how the final product is totally – if not wholly – a product of the methodology and protocols that are in place. So much of everything that Black Americans have done is driven by Black sociality, right? It's not like the sociality shapes the mediums, the mediums shaped themselves to sociality. If you talk about jazz for example, you talk about improvisation. Yeah it’s the formal methodology but it's completely bound up with ideas of Black sociality you know? It's like the instrumentalization in the form of critical aspects of Black sociality.

It seemed to me that part of the problem of cinema world I was participating in was that all the methodologies were wrong you know? At the end of the day they didn't seem to have anything to do with Black sociality.

Did that kind of steer you towards your art practice and the kinds of films you’re making now?

Right about at the moment where you could say I achieved some sort of professional success I just got super disenchanted with it. So I was like really I don't really want to shoot other people’s films. Technically, formally and aesthetically I couldn't figure out how to go forward. At a certain point I just said I'm not shooting anymore. So I told people I retired from shooting. And I'm just concentrating on directing. And basically trying to realise what I've come to call Black visual intonation. Over the course of three or four years you know I was just increasingly disenchanted. And at a certain point I threw my hands up and said, “Ah fuck this shit. I'm just going to do my art thing.”

It’s interesting that you stepped out from behind the camera and started to form this visual language – that Black visual intonation you’d been thinking about and gathering over time from the architecture days through to your time in the film industry. Your art practice now seems to address that cultural ownership and property, using archives and imagery sourced from the Internet.

Personally I'm a little resistant to framing what I do as archival. Yeah that's a curatorial dimension to it for sure but I mean in art – you’re curating the notes if you're a musician. If you're a painter you're choosing the pigments you use. You always have to make choices. And in terms of film the raw material of film is blocks of images. So I've been mining repositories like YouTube and other social media. I'm not sure social media’s an archive in the classical sense. Typically archives are repositories of material that first of all are not public. They're generally private and you need permission to access.

In terms of my work appropriating other people’s works, that just goes back what I said in the beginning. Black sociality. Part of the ontological and psychosocial dimension of Black being, meaning, how Black people operate in the west. We know we weren't human beings when we got here. We were raw material when we got here. So any kind of material expressivity becomes problematized because we didn't control material right?

Nam June Paik said, “The culture that's going to survive in the future, you can carry around in your head.” The culture you can carry in your head. We're super strong culturally in those spaces where our culture was carried on our nervous systems: music, oratorical stuff, dance. Those are all things that you carry in your body. So if you're enslaved in Africa, put on a ship, brought to the Americas, you can carry those things with you.

But all this sort of material expressivity – painting, sculpture, architecture – erodes really fast because you can't carry a building when you're on a slave ship. And even if you’re emancipated from the slave ship and introduced into this new alien environment, whether you're on a chain gang, plantation, prison, doesn't really matter. You can continue to sing to sing. You can continue to talk. You can continue to dance.

You’ve talked before about an idea of dance and music and Afro-American expressivity as ‘glamouring’, and I really liked that description, as a kind of way to deflect from abusive power.

Huh. It's funny. I haven't talked about glamouring for a while. It was a while ago. If you started talking about the particularities, the particularities of how Black people have been able to not just survive but thrive in a very antagonistic environment. It's the fundamentally the relationship between Blacks and whites in America at least. It's fundamentally S&M really. There's a top and there's a bottom, and it’s consensual. But Black people are in the fixed positionality, in that dynamic we're on the bottom. So our survival always depended on our ability to be able to, as I say, glamour the top you know what I mean? How do you control interaction from the bottom?

Much of Afro-American expressivity is not only bound up with the things I've been talking about but it's bound up with surviving. Like how do I make myself indispensable? How do I make myself magical? There's a weird internal tension between wanting to express how we actually feel and also wanting to entertain the alien or the Other. You know like how do you control by entertaining? So a lot of us dancing and singing and these kinds of stuff is very do or die.

Well, let’s talk more about music. You’ve been quoted many times as saying you want to make Black cinema with the same power of expression the same as other art forms within the Black community. How does this notion continue to shape and influence your art practice?

First of all music is the one sort of Black American creation that’s sort of undeniable. It's the one thing that sort of everybody agrees on, that it’s great. Not just great but deep and diverse, so much that it's almost paradoxical.

If I played you some music you never heard before you could generally just say, “Yeah that's Black music.” But at the same time if I asked you what black music sounds like, it would be too diverse to reduce it to a single thing. Like Billie Holiday is clearly Black music as is Jimmy Hendrix as is Bob Marley as is John Coltrane. You could go on and on and on. But none of those things sound like anything alike. You would never confuse those things with one another right? There’s an inherent, undeniable power of our music. And not just that it’s powerful but it's something that we created, that we own. And owning things is a big deal for us because we were owned. The process of ownership is fundamentally a deep kind of thing.

Now the other aspect of it is like it's actually a formal model for certain kinds of possibility. It’s not just that we created it, it’s dope and that we have a kind of ownership of it. It also is a powerful model of certain possibilities you know. That sort of mantra that I have of wanting to make Black cinema that can match the power and alienation of Black music should be more properly extended to Black visual expressivity.

This is complicated, and requires a more complex infrastructure to practice in the space of visual or pictorial expressivity than music.

Like I can just sing a song, I can carry tunes in my head. I can dance. But if you think about pictorial expressivity, you don't really carry a picture in your head. Or you can, until I want to share that picture with you. Either I have to draw it out which I may or may not have the skill to do. Or I have to describe it to you.

It makes the whole proposition of Black visual expressivity powerful because it's a space that we've been denied. Moving into that space is not necessarily about the thing. It's not about architecture. It's not about cinema. It's not about painting. It's about demonstrating concrete ties an immaterial that can be known as Black aesthetics, Black values of beauty, Black philosophical ideas. How does that become concrete? If you can make that thing concrete, you are demonstrating the actuality of the thing which exists in our heads.

This matters so much to us because Black people created culture in freefall. I think that's a big part of the charge why you're seeing a real kind of insurgency and emergence of Black artists in the world right now because it's been a space that's been denied to us for so long, you know?

All of a sudden now people videotape everything. Not that there's this groundswell of violence towards Black people that's now being videotaped. No, that violence has always been part and parcel of American society. It's just that they're videotapes of it now.

I first watched your film, Love is the Message at the same time I was reading Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me and for me, each of these works strongly influenced my reading of the other one. Do you see the kind of wrestling of control that both you and Coates have explored as artists part of that insurgency or groundswell of a movement?

I’m resistant to binding up my artwork with the Black Lives Matter movement. I certainly wouldn't deny for a second that they are all bound up in a particular moment for example. But I never really saw Love is the Message as activism per se. Even though people often times look at it and they frame it as activism. It's not a dismissal of activism. I am very interested in the reasons that underlie why we do what we do, which often times I don't think can be reduced to political explanations. I think they're more complicated than that.

Tell me about that moment, then, and how Love is the Message came to be? It was completely made when there was this tidal wave of heretofore undocumented or mediated examples of Black people being abused.

I remember the first time somebody told me they're going to put cameras in telephones. I said that's the dumbest idea I've ever heard in my life. But it's been transformative because all of a sudden now people videotape everything. Not that there's this groundswell of violence towards Black people that's now being videotaped. No, that violence has always been part and parcel of American society. It's just that they're videotapes of it now and with social media people can post those things.

Shortly after the death of Trayvon Martin who was killed in the typical, irrational crazy fashion that white infrastructures kill Black people, a tipping point was reached where people realized they have the cameras in their phones and that they can actually videotape these instances. Somewhere between Facebook and YouTube hitting a critical mass, people started posting these things. There was this moment where there was a wave of footage. It seemed like every week there would be a new video of a black person literally being murdered.

And as I tend to do I just save anything that I find interesting or disturbing: stills, articles, video. I was just throwing these things in a file, not really thinking about doing anything with them. The critical thing was this video tape which you’ll see in the film, the woman who got arrested with her two kids. The police are telling her to back down. And there was something about that video that made me cry. It broke me. None of the other footage broke me like that.

I was working on a job, I was bored. So I just laid those things out like in two or three hours while my editor was doing something else and the whole thing just put itself together. I don’t feel like the gesture itself was fundamentally political, much more emotional or just a visceral reaction.

It's easy to talk about the sociopolitical dimensions of Love is the Message. But I've always been obsessed with things like Bernini, you know. It’s very continuous with things like Bernini and Michelangelo, particularly like the treatment of the bodies. The Rape of the Sabine Women, Caravaggio's pictures of Jesus. The fact he used pimps and prostitutes. These classical things were political in their time. We just lose the political part in history. But what is fundamental is human interaction, what's going on.

My thing is fundamentally about addressing black people. And I've said that time and time again, which people sometimes want to collapse or simplify to like, “I have a problem with white people”. I'm very happy if anybody likes what I do, but I am addressing black people. It's who I'm speaking to. Everybody else basically gets to listen in.