The story of Badu Gili

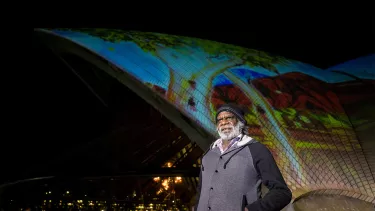

Badu Gili lights the sails every night with First Nations art

When the sails of the Sydney Opera House were illuminated with First Nations art for the first time, audiences were transfixed. The event was Songlines – named after the spiritual paths that snake across Australia in Indigenous lore – and materialised in spiralling colours and vibrant symbolism on the sails of the Opera House during Vivid LIVE 2016. The projections ran for barely a month, disappearing as quickly as they emerged.

It was to the relief of viewers everywhere when Songlines was born again the following year as Badu Gili, this time a nightly year-round sunset projection viewed by more than 160,000 visitors in person visitors, and another 620,000 online in its debut year. Launched with new artwork in July 2018 and animated in collaboration with Yakkazoo, Badu Gili has given First Nations artists the opportunity to present their stories to an unprecedented international audience. We talked to three of this year’s artists about those stories, and what inspires them to create.

Meet this year’s artists

Penny Evans, Gamilaraay

It’s hard not to be struck by the sheer materiality of Penny Evans’ work. Deep, coloured incisions carve their way through ceramics like scars, crafting detailed patterns that reference the terrain of her ancestral lands in Northern NSW.

“It comes down to the landscape…an observance of my landscape out there on country,” says Evans. “The ground, the cracked mud of our waterholes, the coolamons, the trees.”

She’s honed her distinctive style over 35 years with countless exhibitions and awards, but Badu Gili is the first time her pieces have been digitised. For an artist whose work is so tangible, the transformation from original ceramics to light projections isn’t so much a direct facsimile, but rather a reinterpretation. But the results are equally as striking: bold colours that almost float across the sails, repeated patterns that expand into infinity.

Evans’ ceramics are as much objects of beauty as they are a reminder of colonisation. Her work is inextricably tied to the ongoing process of understanding her Gamilaraay heritage – a heritage that, for too long, has been omitted from Australian history.

“For me, it’s been an investigation of my personal story through to my mother’s story, my grandmother’s, my great-grandmother’s,” she says. “When I grew up in the ‘70s, we knew nothing. We weren’t told anything about anything. We were all in the same boat – blackfellas, whitefellas, everyone was in the same boat around the history of what had taken place."

There isn’t one right way to do an opera. Every work is completely different, it’s a journey into the world the composer has created.

Her work is the product of these ancestral ties: the preservation of Gamilaraay culture for generations to come. The techniques that Evans employs in her ceramics are reminiscent of those used by her ancestors (“they were very enthusiastic carvers,” she says) and by immortalising their ancient lore on the sails of the Opera House, Evans aims to inspire others to seek out the stories hidden in their lineage.

“Hopefully people will look at what I do and they can start to unpack their own histories as well. My opinion is that if we don’t all go and seek understanding and knowledge of ourselves, who we are, where we come from, and connect it to what’s happening in Australia, then we’re just doomed.”

She hopes that Badu Gili will facilitate a renewed understanding of First Nations art and its diversity for a broader audience.

“I want them to see that Aboriginal art isn’t just one thing,” she says. “There’s no one stereotype of art that is Aboriginal. That needs to be thrown out…that just confines Aboriginal people.

Mervyn Rubuntja, Japanangka

Mervyn Rubuntja was always destined to paint.

Born in Australia’s Red Centre, he grew up surrounded by artists – most notably his uncle Keith Namatjira, son of the late Indigenous art pioneer Albert Namatjira – and spent many a summer watching, enthralled, as they worked by the Todd River’s dry riverbed.

“Those artists were really good,” he says. “And I thought to myself: One day I might learn.”

But it wasn’t until he attended school in Hermmansburg that he finally made good on his promise, seeking out mentors who told him to really see the country in all its colour. So he observed, and he painted what he knew: the sprawling landscapes of Alice Springs with their shocks of red plains, broken up only by green foliage and distant mountains sunken blue in shadow.

I paint so the next generation can see for themselves what the land looked like.

The Hermannsburg watercolour style has come to define his paintings today – paintings that, despite their fantastical hues, retain a sense of honesty and loyalty to the land. Rubuntja considers his work a time capsule of the land in its current state, lamenting the rapid encroachment of construction and mining onto once-untouched landscapes.

“For the next generation, things might get worse,” says Rubuntja. “Things like land clearing, building houses…I paint so the next generation can see for themselves what the land looked like. I think to myself: The grandchildren will see that there were no houses there.”

Watching as projections of these paintings glow across the sails of the Opera House, one can imagine the land of Rubuntja’s childhood in all its lush, unmarred brilliance. By displaying his work as part of Badu Gili, Rubuntja hopes to rouse audiences to preserve the land in that state, fighting against its destruction.

“Things can get better, if they’re willing,” he says.

Pat Ansell Dodds, Central Arrernte and Mudburra

There’s a sense of invitation at the heart of Pat Ansell Dodds’ paintings. They feel familiar at first glance, washed in earthy tones and constructed from repetitions of lines and dots. But spend a second longer and they begin to take on a life of their own, daring the viewer to interpret the symbolism belying their intricacy. And there’s certainly no shortage of symbolism.

“When you see that red ochre paint, that reminds me of where I come from,” she says of one of her works featured in Badu Gili this year. “And the other painting is about a woman collecting passionfruit along the river.”

Her work is borne from a deep connection to her dual Central Arrernte/Mudburra heritage, and pays homage to the women at the bedrock of those cultures, as well as the women in her own lineage.

“I’ve had a very good upbringing with my aunties and my grandmother. I’ve been able to learn from them about my culture, about central Australia. They told me a lot of stories connected to me.”

We’re people that have knowledge about who we are. And what we’re doing here is sharing it with the rest of Australia.

But it wasn’t until a death in the family that she took up her own artistic practice.

“I started after I lost my younger brother, who was the artist,” she says. “When he passed away, I thought I needed to paint our culture so I could share it with my children and grandchildren. And I felt in my heart it was so important to do that, even though it took me a long time to really paint the way I do today.”

As such, personal history isn’t just a thematic springboard for Ansell Dodds, but embedded into the very intent of her paintings. The result is artwork imbued with an inherent sense of intimacy, inviting viewers of Badu Gili to engage with her ancient traditions and customs.

“Try and understand we’re living in a modern world, but in our hearts and our heads, we are very strong-cultured people.

“We’re people that have knowledge about who we are. And what we’re doing here is sharing it with the rest of Australia.”