The blessing (and curse) of Bach’s Goldberg Variations

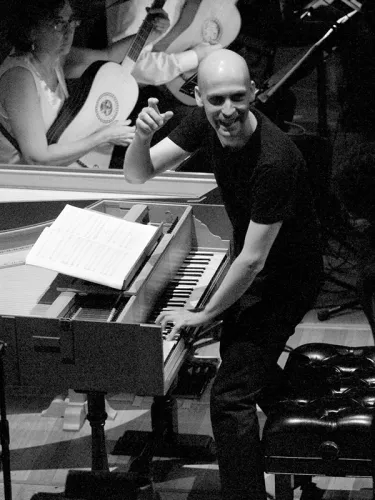

Harpsichordist Erin Helyard and the ACO premiere a rare orchestral arrangement

Playing Bach’s Goldberg Variations is like performing Hamlet. Everyone knows the lines, they have their favourite adaptation (the Kenneth Branagh version, or Ethan Hawke?), and they’re always hanging on to see how you deliver that “To be, or not to be.”

Keyboardist Erin Helyard has been practising the seminal works for twenty years, and will be performing them for the first time with the Australian Chamber Orchestra this August – on the harpsichord for which they were written.

“There’s a wonderful phrase by the writer Harold Bloom – ‘the anxiety of influence’. You feel the weight of all these amazing artists who have trod that path before you … I definitely feel that anxiety there,” says Helyard.

“For most music lovers it’s become famous through the two recordings of Glenn Gould, and rightfully so. It’s also been in film, the aria in Silence of the Lambs ... It’s always brought up to symbolise purity or some sort of simplicity.”

And in addition to that, Hannibal (2001), Before Sunrise (1995), Sofia Coppola’s Somewhere (2010), Slaughterhouse-Five (1972), The English Patient (1996) and Solaris (2002).

The thirty-one pieces, now affectionately referred to as ‘the Goldbergs’, each hold their own character and genius. Published in 1741, Bach wrote them to ease the insomnia of Russian diplomat Count Hermann Karl von Keyserling. It's believed that Johann Gottlieb Goldberg was the first to perform the works. Over the centuries they’ve spawned an immeasurable number of versions, some inviting praise and others controversy, including transcriptions (the iconic Glenn Gould piano recordings), arrangements (by a Japanese saxophone quintet), and interpretations (Max Richter’s eight-hour Sleep).

The harpsichord isn’t an instrument recognisable to most people’s ears. For Helyard, director Richard Tognetti and the ACO, Bernard Labadie’s arrangement transcribes the arrangement to an ensemble for strings and harpsichord, with taste.

“It’s pretty much a literal arrangement of the keyboard work with some discrete filling-in. There are some other arrangements for orchestra that date from the ‘60s and the ‘70s, but this one certainly keeps with 18th century principles. It’s as if someone from the period arranged it.”

“Some composers in the 20th century have arranged it with the full forces of the symphony orchestra – modernising it – and with this version we haven't really done that.”

Not all arrangements are listened to favourably by fans of Bach, and the definition of ‘arrangement’ itself can be questioned (technically, piano performances of the Goldbergs, like Gould’s, are transcriptions of the original harpsichord works).

“I would argue actually that modern pianists are transcribing the Goldbergs,” says Helyard. “They have to make adjustments for the modern piano, but they’re not necessarily changing the musical text very much. But a good arrangement does change the text quite a bit to suit the new forces for which it’s arranged.

“A transcription is a bit more literal, and an arrangement is a bit more artistic.”

He goes on to praise Leopold Stokowski’s arrangement for full symphony orchestra (a version which purists may hate). This, however, is just the tip of the ‘Goldberg’: there’s Jacques Loussier’s version for jazz trio; Karlheinz Essl’s 2003 arrangement for strings and live electronics (read: laptop); and Joel Spiegelman’s 1988 transcription for the Kurzweil synthesizer.

The ACO’s programming for the evening is as experimental as much as it is respectful: opening with Stravinsky, Adès, the Australian premiere of Labadie’s Goldberg Variations, as well as Tognetti’s own arrangement of the canons (a baroque form where a melody is repeated, overlapped and expanded throughout the piece) that he found scrawled at the back of Bach’s original score for the works.

In an interview with online magazine VAN, harpsichordist Mahan Esfahani describes the state of his instrument today: “I’ve heard leading figures in the harpsichord world give recitals that were played as if someone had died.” Esfahani and his colleagues like Helyard are confident the humble keyboard is making its comeback.

“Because the piano is much louder it’s had a longer tradition of being played in recital halls,” says Helyard. “You don't really hear a harpsichord as much as a piano. And if you think about it, when you grew up, there were a lot of pianos about but there weren’t really many harpsichords.

“Increasingly you see harpsichords in institutions like the Sydney Opera House, the ACO, high schools, universities … It’s much more accepted. And the sound of the instrument, we’ve gotten used to it and come to appreciate the beauty of it.”