Steve Reich Reorchestrated

After three decades, the composer returns to the orchestral form for a new work with the Sydney Symphony

“I don’t go to many orchestral concerts at all. Whereas the ensemble, to me, is the center of musical life that I live in,” said Steve Reich. It’s been over thirty years since the composer wrote for orchestra. He broke that with his latest composition in late 2018, first at Los Angeles’ Walt Disney Hall and shortly after, at the Barbican in London. Now it’s Sydney’s turn, when Music for Ensemble and Orchestra makes its Australian debut at the Sydney Opera House.

This co-commission with the Sydney Symphony Orchestra will be performed mid-February in the Concert Hall, pulsing between Czech composer and theorist Leoš Janáček’s Taras Bulba (1918) and the famed Concerto for Orchestra (1943) by the Hungarian Béla Bartók. It’s an intelligent program featuring contrasting minds and times: mid-century Central Europe alongside contemporary America, and the Concert Hall's Grand Organ as part of Taras Bulba.

International counterpoint

All three composers have laid foundations for respective musical movements—Reich for contemporary minimalism, and Janáček and Bartók for the introduction of European folk music to the classical world. As ethnomusicology—the study of ‘cultural’ music, notably outside of the Western world—became the prism through which music was understood and contextualised, ethnicity, national history and other markers of identity began to infiltrate the sound and meaning of classical compositions in new ways. Indeed Reich himself has been hugely influenced by Bartók’s methods as well as by Janáček, Igor Stravinsky, and rhythms from further afield—African percussion and the Balinese gamelan in particular.

Reich is known for his prolific work for ensemble (Music for 18 Musicians, Electric Counterpoint, and Double Sextet which won him the 2009 Pulitzer Prize for Music) which makes his return to writing for the orchestra that much more exciting. The Desert Music and The Four Sections are just two highlights from his orchestral repertoire; music that is filmic, ripe for narrative and visuals.

From a technical and structural perspective, Reich’s orchestral compositions are a musicologist’s dream: deft in the strategic isolation of parts and voices, allowing them to shine alone first, then ultimately being woven together in unusual ways using the hallmarks of his opus—interlocking, canons, pulses.

“We are corporeal beings and of course pulse is part of who we are,” says David Robertson, Chief Conductor and Artistic Director of the Sydney Symphony Orchestra. “Steve Reich gradually brought this back in so many different and subtle ways. And his writing for the orchestra is so marvellous that it’s unusual that it’s not the normal thing.”

Music for Ensemble and Orchestra, like Bartók’s Concerto that precedes it in the programme, takes a five movement arch, peaking in the centre with symmetrical elements either side. Principal strings and woodwinds, two pianos and two vibraphones form the ensemble in this case, and four trumpets and an orchestral string section have been added.

Reich’s orchestral compositions are a musicologist’s dream: deft in the strategic isolation of parts and voices, allowing them to shine alone first

Facts

- Steve Reich was the first composer in residence at Sydney Opera House in 2012 as part of The Composers series.

- Electric Counterpoint was included in the video game Civilization V as one of the “great works of music”.

- Björk included Vermont Counterpoint in a 2017 mix.

- Three Movements for Orchestra was featured in The Hunger Games.

- Donald Trump considers himself as a fan.

Rearranging the stage

Reich’s work takes on a distinctive flavour when written for orchestra. While embracing the fullness of more instrumentation and parts, the ensemble of soloists is still the star and the home for melody. “My orchestra mainly provides harmonic support for what the ensemble is doing, so their functions are distinct”, he says. This shows off the different sections and capacities of the instruments as if they were soloists, again just like the Concerto—strings and mallets for Reich and drums, oboe and bassoon for Bartók.

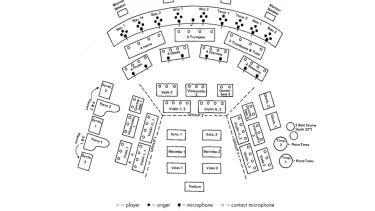

In writings from 1990, Reich published his thoughts on size and seating arrangements of orchestras in order to get the best out of players and sound. Through trial and error, over time he has favoured the size of a full classical, rather than a romantic orchestra: “The gargantuan string section may be appropriate for Sibelius, Mahler and Bruckner (and several neoromantic composers today), but I have found that it is much too overblown for me”.

Interlocking melodies

Reich rezones the orchestra, the most notable change being the mallets (marimbas, xylophones and vibraphones) placed in front of the conductor to temper any acoustic or visual delay.

He has often changed instrument and player placement to suit the work at hand. For his 1983 work The Desert Music for orchestra and voice (performed by the Sydney Symphony with David Robertson in 2016 alongside Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring), he chose to reseat the strings in smaller groups and different rhythmic positions to allow them to follow their section leaders differently. This elasticity is key for the composer, though Reich notes it may not always be accepted by the musicians:

“I would encourage all composers to rethink the orchestra in terms of forces and placement in order to best realise their musical ideas. Whether such rethinking along with the added need for considerably greater rehearsal time and electronics, will be welcomed by orchestras is clearly another thornier issue.” (from On the Size and Seating of an Orchestra, 1990)

This is not the first Australian premiere of Reich’s work to fill our Concert Hall. In April 2012, Variations for Vibes, Pianos and Strings was performed as part of a program spanning more than four hours under the baton of conductor Roland Peelman, now Artistic Director of the Canberra International Music Festival. Next for Reich is an immersive performance in collaboration with the painter Gerhard Richter in New York City highlighting the composer’s take on musical architecture—repetition, minimalism, patterns.

It’s clear that Reich’s career and back catalogue are unparalleled. Many interpretations and applications of his work (some in unexpected places) have allowed his music to amorphously grow into its own, prompting questions about the line between classical and contemporary music, art feeding other art, the power of music, and more. Here are just three that help to answer these in the blurriest of ways.

Choreographer Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker

Belgian choreographer Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker has set many of her works to Steve Reich’s music. Notably Fase (1982), set to four of his pieces and Rain (2001), set to Music for 18 Musicians (1976). They are regular creative collaborators, bringing together Reich’s sense of structure and Keersmaeker’s fluidity on stage in a contemporary dance context.

From the original 2011 programme: “The two arts coalesce and fuse right up until the last exhausted breath, their invisible mysteries revealing an exhilarating work where mathematics rhymes with emotion, volatility with exactitude and unity with diversity.”

Her dance company Rosas has also set dance works to pieces by Béla Bartók and other classical composers.

Clapping Music App

The Steve Reich Clapping Music app was launched in July 2015 as the result of an English government funded digital arts grant with the London Sinfonietta and other partners.

The free app was designed as a game set to Reich’s famous piece, and was used to research how rhythmic skills are developed within a digital technology context. Users tap their device in time with the patterns of Clapping Music, and through all of their variations with increasing difficulty. Scores are achieved based on the closest accuracy to the piece. The app also served to show the educative power of music and noted an increased appreciation and understanding of the minimalist genre by users.

Reich Remixed (1999, 2006)

Reich Remixed was released in 1999 with a slew of remixes by the likes of Howie B, Ken Ishii and Nobukazu Takemura, highlighting the voracious diversity of Reich’s catalogue and how many artists he has influenced. In 2006 another version was released including this version of Drumming by Four Tet.