Tognetti & Greenwood talk Indies & Idols

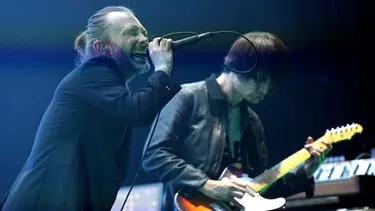

Anwen Crawford talks to ACO Artistic Director Richard Tognetti and Radiohead guitarist Jonny Greenwood about “bringing a generation of contemporary composers together with their influences”.

Jonny Greenwood's Suite from There Will Be Blood features in Indies & Idols, which plays in the Sydney Opera House Concert Hall on Sunday 16 June. The following is an excerpt of Anwen Crawford's essay from the show's programme.

“This program does not look friendly on paper,” laughs Anna Melville, artistic administrator of the Australian Chamber Orchestra. Cast your eye down the running order and you’ll find “a lot of names”: consonant-heavy Polish names that carry with them the faint threat of atonality and avant-gardism, and other names that may look familiar but are possibly, in this context, out of place.

Melville says “this is one of those programs that’s greater than the sum of its parts. It’s really about how it’s all going to work together.” And that, Artistic Director Richard Tognetti says, is “the idea – this was really the genesis of the program, not any particular piece – of bringing a generation of contemporary composers together with their influences”. Indies and Idols is a program about musical inheritance, inheritance over time and across boundaries that may be more porous than they first appear. Some of those boundaries are between the “classical” and “popular”, for instance, a boundary that Jonny Greenwood of Radiohead thinks has “been blurred for decades”.

Of the three contemporary composers whose work is included in this program, it is Jonny Greenwood who has the most well-established relationship with the ACO. His work has featured in the Orchestra’s concert repertoire times, and in 2012 he undertook a three-month appointment as the ensemble’s composer-in-residence, during which time he wrote Water, a “hypnotic piece”, in Tognetti's words, for flute, upright piano, chamber organ, tanpura and string orchestra.

“I was so lucky to write for them,” Greenwood reflects, “and to hear them perform and practice. Such a privilege. They have this intensity and energy – like an insane mixture of enthusiasm and certainty – which makes for the most overwhelming performances.” Tognetti is equally complimentary, enthusing about Greenwood’s 2011 homage to Krzysztof Penderecki, 48 Responses to Polymorphia, which he calls “a brilliant work”.

“Violins are so glorious,” Greenwood says, when asked about his facility for strings, the unusual, dramatic arrangements he writes for Radiohead, and his own compositions for film and orchestra. He learned to play the viola as a teenager and was a member of the Thames Vale Youth Orchestra. “I was once taught that all instruments aim to replicate the human voice – to sing. With string instruments, I think they surpass the human voice. Or put another way, I listen to lots of classical singers, and wish they had the warmth, agility and beauty of, say, a cello.”

Though he is best known as a flamboyant electric guitarist – and an indefatigable multi-instrumentalist – Greenwood’s lengthy engagement with classical music is well documented. He was a teenager in Oxford during the 1980s when he first heard Olivier Messiaen’s 1949 Turangalila Symphonie, and, as he told the aforementioned Alex Ross in a 2001 New Yorker profile of Radiohead, “I became round-the-bend obsessed with it”. So much so that he would eventually teach himself how to play the ondes Martenot, a rare and early electronic instrument that featured in Messiaen’s work and which can be heard, in all its wailing weirdness, on several recordings by Radiohead, including “How to Disappear Completely” (2000), a song Tognetti singles out for the vertiginous beauty of its string arrangement.

I was once taught that all instruments aim to replicate the human voice – to sing. With string instruments, I think they surpass the human voice.

Greenwood also had a formative encounter with the music of Penderecki, which he was introduced to during his brief tenure as a tertiary-level music student. He quit his degree in a matter of weeks after Radiohead signed a recording contract with EMI, but “in those few weeks I was lucky enough to be shown a Penderecki score, and played Polymorphia, by a tutor,” he recalled. “I didn’t know you were allowed to be that free, and you could just think of these 48 musicians as being able to do anything. Suddenly all these possibilities opened up.”

It is this liberation from the orthodoxies of both popular and classical music that Greenwood has brought to his career in composition, which is already extensive, encompassing eight film scores and nearly a dozen concert works. Suite from There Will Be Blood is arranged by the composer from his score to Paul Thomas Anderson’s 2007 film There Will Be Blood, a dark drama of the American West starring Daniel Day-Lewis as oil prospector Daniel Plainview. If, as Tognetti says, it has been the achievement of composers such as Penderecki to express the violence of the 20th century through sound, then it is no surprise that Greenwood’s score bears Penderecki’s influence, giving voice as it does to the rise and fall of a ruthless fuel baron at that century’s dawn.

There Will Be Blood was Greenwood’s first film score for Anderson; he has since scored an additional three films for the director, including last year’s widely acclaimed Phantom Thread. Suite from There Will Be Blood is striking in its range of mood and textures: descending glissando lines that sound, in their sinisterness, like the musical equivalent of Salvador Dali’s melting clocks; tense and bristling pizzicato sections; yearning moments of melody. It was written, Greenwood says, “mostly to stills of the landscape and the script. There were a few scenes to go on, too. The sweeter music was all written about H.W. – Daniel’s child in the film – and the bigger, darker music was all meant to be for the landscape. And one cue was, essentially, Jaws – Daniel as voracious oilman buying up all the land.” Listen and you can hear it: John Williams’ famous two-note shark theme transposed into the opening moments of Greenwood’s Suite, fit for another kind of carnage.

Anna Melville, too, notes the correspondence between the Polish composers on this program who challenged – and, in Penderecki’s case, continue to challenge – the structures of the academy and “this next generation of composers, who have access to people and influences outside the traditional conservatoire world. Greenwood, she says, with his range of influences, “isn’t separate as a composer from who he is as a musician in Radiohead”.

The man himself would – to some degree – seem to concur, amenable to the suggestion that his work in composition, which is characterised by a lively tension between individual melodic lines and the ensemble en masse, has been influenced by his time as a member of a band. “I like the complexity of all the individual voices, and any element of controlled chaos that ensures no two performances - or even two bars - can sound the same,” he says. “Unison playing makes me think of keyboard presets. I guess maybe this does come from the mentality of playing in a band. Or perhaps because in the first Radiohead string section we could only afford one cello and one violin – and it’s been a long wait to get access to a whole room of players.”