Through time and space: A brief history of sampling

The Avalanches and DJ Shadow on mastering music as its own instrument

Chandra Oppenheim was just 12 years old when she released her first LP, an experimental post-punk album called Transportation that was fueled with the energy of New York in the early 1980s. She stayed a musician, composing beautiful but barely-known songs.

Until 36 years later, when The Avalanches sampled her voice.

“I feel like I have to ask some friends of mine which philosophers I should be reading, because I can't quite make sense of it,” Oppenheimer told Thump when asked what it was like to hear her 12 year old voice mixed into a just-released Avalanches track. Like a satellite that sling-shots around a planet, her song has been propelled into a whole new galaxy.

If the internet is the world’s biggest copying machine, then making music by sampling the music of others is perhaps the most contemporary phenomenon of contemporary music. There’s nothing new in saying that everything has been done. It’s been 100 years since Marcel Duchamp unveiled his urinal and art has been recycling itself ever since.

While sampled music is ubiquitous, for some it still has a whiff of copy-and-paste illegitimacy. It was only in 2014 that the Grammy Awards allowed songs that use samples to be eligible for major songwriting categories. And yet listening to Robbie Chater of The Avalanches – the Australian band who took sampling to new heights with its debut album Since I Left You – there are many more layers to each borrowed orchestra swell and muddy kick drum than initially meets the ear.

Robbie Chater, The AvalanchesIt’s moments like that that’s why we do this. For me that’s what it’s all about.

Chater says that the whole concept of Wildflower, the Avalanches' second album, was to evoke a feeling of a homemade record - the type of work created by someone without backing of a major label who just wanted to make music. “[Oppenheim] made that record [Transportation] when she was 10 to 12, with this punky attitude,” he tells Backstage. “It fitted with what we were after.”

Permissions were sought – since becoming mainstream in the early 1990s sampling has only been possible with the copyright owner’s consent – and the song, named Subways in tribute to the original, became one of Wildflower’s instant hits. Chater says the band got to meet Oppenheim when they played a few weeks ago in LA. “She was in the crowd with her 10 year old daughter, her daughter was the same age she would have been [when she released her LP]. And hearing everybody singing to that song, that generational thing, the way music has travelled through time and space, from her to us and back out through us to her again.

“She came backstage and we looked at each other and no one knew what to say. So we just hugged. It’s moments like that, that’s why we do this. For me that’s what it’s all about.”

Sampling, in production terms, is simple: a musician takes moments of a composition – a few piano chords, a fluttering trumpet after-thought, a particularly funky drum loop – and rearranges them in a sort of musical collage. Producers discovered that ‘found sounds’ seemed to flow effortlessly under spoken verse, and the technique kickstarted a cultural shift. In the 1980s Afrika Bambaataa and Soulsonic Force rapped over a Kraftwerk drum machine loop on Planet Rock. In the 1990s, jazz became the preferred sound source, and A Tribe Called Quest riffled through collections of Cannonball, Coltrane and Miles.

As we hit the early ‘00s, beatmakers stopped digging in dusty crates and took to their video games instead. Slum Village’s Raise It Up bounced between the digital arpeggios of Extra Dry by Thomas Bangalter of Daft Punk (also heard on the PlayStation game Midnight Club II). Wiz Khalifa returned to early trance by rapping over Alice Deejay’s Better Off Alone, maintaining the tempo but flipping the beat. Kanye West, Chance the Rapper, Die Antwoord and Azealia Banks have all sampled Aphex Twin.

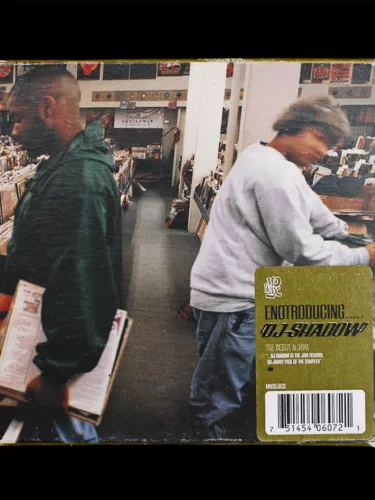

A watershed moment occurred in 1996, when DJ Shadow’s debut album Endtroducing..… was released. It was the first album composed entirely, more or less, from sampled content, most of it from vinyl records. Groundbreaking and genre-shaping, it spawned a scene of beatmakers in labels like Stones Throw and Brainfeeder that recognized rap music didn’t need to be all about the rapping.

Shadow, whose birth name is Josh Davis, has remained at the forefront of electronic music, reworking the palettes of rock, funk, electronic, jazz and much else into an oeuvre that spans five albums. To the casual listener his most recent, The Mountain Will Fall, features far fewer samples than were used in his early work. But Davis says there are probably even more.

“I’ve learned to think about sound very differently than I used to,” Davis tells Backstage. “When I first started making records, sampling was very new. It was a new art-form. In the late 80s and 90s, ‘real music’ was all you heard on radio. Rock groups hated sampling, the music press hated sampling. Nobody in RnB did it.”

Meanwhile artists like Prince Paul and Marley Marl were mastering the craft of sampling, Shadow says. Peter Gabriel was experimenting with a Fairlight 6000 (an Australian-made digital synthesizer) to shape the sounds of the 80s. By the 1990s sampling had become mainstream. Hip-hop absorbed it, and then abandoned it, and then it came back.

“What all those things have taught me, as I have matured and thought about music, is that nowadays everything is a sample,” Davis says. “Sampling is editing. And a lot of music making is editing. There are a lot of sounds on Mountain that are samples, but that don’t sound like samples.

“If you think samples only come from 45 [RPM records] then I sample less. If sampling is literally the editing or manipulation of sounds, then I’ve gone from riding a tricycle to a full blown sports car.”

A case in point: on Soundcloud, someone has uploaded the Windows 95 start-up sound – the original composed by Vivid LIVE godfather Brian Eno – slowed and stretched by 4000% into a four-minute ambient masterpiece – it’s almost at one million plays.

Layers of identity are constructed when musicians sample, re-sample and de-sample through the decades. Eddie Murphy’s voice in the 1983 film Trading Places was sampled in 1991 by house legends Masters at Work, and then 20 years later MikeQ sampled Masters at Work sampling Eddie. In 2014 Björk collaborator Lotic deconstructed the same sound in Heterocetera.

And then last year Apple kicked up a Twitter war when the same sound appeared in its advertisement to launch the iPhone 7.

Ben Marshall, the Head of Contemporary Music at Sydney Opera House and the festival curator for Vivd LIVE says both The Avalanches and DJ Shadow's debut albums were immediately recognised as epochal works. "Endtroducing and Since I Left You were profoundly evocative records," he says. "Their sampling managed to bring a sense of playing with time and legacy, even when the releases were brand new."

While the sound of Shadow’s sampling has evolved, there’s a greater consistency with the sound of The Avalanches. Chater believes one difference in the composition of Since I Left You and Wildflower is that the latter involved more surfing around YouTube rather than flipping through records in record stores. But if the mechanics are different, the artistry is the same – sitting down and listening to strange old music.

“It triggers something in me that makes me feel a certain way. It’s a feeling there that I can expand on,” he says of the sounds he’s looking for.

Sometimes he or his fellow band member Tony Di Blasi will hold tracks in their mind for years, waiting to find the other track that completes the idea they have in their minds. In one instance, that track was Madonna’s Holiday. Of the hundreds of samples on Since I Left You, the unmistakable bounce of Holiday adds an instant dose of 80s pop to the album’s second track, Stay Another Season. The process of getting the clearance was long and involved, but the band was convinced it was essential.

“We were sampling Latin travel holiday records. In the 50s exotica was really big. People would listen to Hawaiian music at their backyard barbeques, and the idea of using Holiday came to us. It started as a bit of a joke but then we decided to give it a go. It took a lot of attempts, but we got there.”

“That entire album was about taking a journey,” Chater says. "The spirit we were chasing was that beautiful moment between happy and sad. That feeling of melancholy. For me creating music is expressing myself from the heart and trying to get how I feel out there. A sample is just the instrument that I use.”

If sampling is literally the editing or manipulation of sounds, then I’ve gone from riding a tricycle to a full blown sports car.