Testing the Concert Hall’s acoustic reflectors

Published

“Every concert hall has a story of its own, but this one is pretty special.” - Gunter Engel

Try this experiment at home. Record a conversation on your smartphone and then play the recording back to yourself. Notice what’s different? The sound in the recording seems fuller and more textured than the real thing.

It seems counter-intuitive. Nothing should beat a live performance. So why does the recording sound so different?

The answer lies in the way our hearing focuses on sounds that our brains think are the most significant – a capability that has evolved over time, promoting human survival by helping avoid predators and locate prey. It helps explain why music in a concert hall sounds better than at an outdoor festival (and why the sound can seem muffled if you’re sitting right at the back). And it’s one of hundreds of laws of acoustics – a complex mix of geometry, architecture, physics and neuro science – that must be mastered to make a hall sound beautiful.

Sydney Opera House, one of the world’s most famous music venues, has long had a problem. Everyone loves the building, but not everyone loves the way it sounds, especially in its largest venue, the Concert Hall, home to the Sydney Symphony Orchestra, the Australian Chamber Orchestra and a stage for everything from rap artists to world-famous classical orchestras (Kanye West played in 2006. The Berlin Philharmonic played in 2012). Some feel the acoustics in the Concert Hall lack power. Many think the sound is different depending on where you are in the room. It’s said the hall is simply too big and its ceiling is too high. In 2014 actor and director John Malkovich said an airplane hangar would sound better.

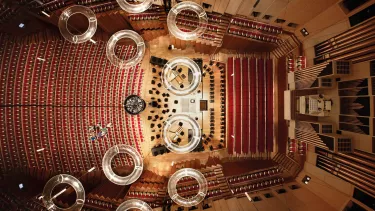

But after 46 years of mixed reviews, the Concert Hall is finally getting a major upgrade. Theatre machinery, grid systems and the air-conditioning is all getting replaced. Better access and more room is being made available for people in wheelchairs. The biggest change will be to how the hall sounds: the stage will be lower, the walls beneath the boxes will tilt differently and new acoustic reflectors will replace the plastic ‘donuts’ that have been hanging above the stage since the Opera House opened in 1973.

On its own it would be a massive project. Yet it’s just one of six projects that form the centrepiece to the Opera House’s Decade of Renewal.

“Improving the acoustics in the Concert Hall is a critical part of Renewal,” says Sydney Opera House CEO Louise Herron. “It’s been an issue for a long time. It’s been an issue that’s never been solved and if we can solve it that’s a wonderful thing.”

November, 2016 and there’s more pressure than usual during a rehearsal of the Sydney Symphony Orchestra. On stage the players are working their way through Tchaikovsky and Mozart, conducted by Israeli violinist Pinchas Zuckerman. Suspended above are 28 giant reflectors, made of wood and shaped like petals of a flower – or maybe rounded guitar pics. Dotted around the empty rows of seats are yellow foam balls that resemble smiley faced emojis listening to headphones.

These yellow foam balls hear sounds just like the human ear and feed the results into the laptop of Gunter Engel. His screen shows a rendering of the hall with dots demonstrating how sound from the stage hit the reflectors and where in the hall they land. Engel and his colleague Jürgen Reinhold work at Müller BBM – a Munich-based acoustics engineering firm. They’ve worked on Moscow’s Bolshoi Theatre, London’s Royal Albert Hall, and the three big concert halls at Rome’s Parco della Musica. Now they’re working on the Opera House.

“Every concert hall has a story of its own, but this one is pretty special,” says Engel (who when asked what music he’s into offers up the Romantic era, especially music by German composers; Schubert, Schumann and Beethoven).

Engel and Reinhold agree that the sharpest criticisms of the Concert Hall is unfair. “The acoustics are actually pretty good,” says Reinhold (who prefers Bob Marley). But the partially vaulted ceiling creates an unwanted reverberation. "We’re looking for the best results we can get,” he says.

Which is the point of the new reflectors, prototypes of which were tested in November 2016. A key challenge is to stop sound disappearing into the void above the stage which makes it hard for players to properly hear each other. Niels Erik Lund is a sound engineer who worked on Copenhagen’s spectacular Jean Nouvel-designed DR Koncerthuset and is now overseeing the works in the Sydney Opera House Concert Hall. Lund (who likes The Beatles, Beethoven and anything that makes him dance) says audiences will immediately appreciate how much better orchestras play, and hence sound.

“It’s a complex process but it’s really a very easy or simple thing. When you hear yourself, you’re able to play much better. The players have been struggling for a long time,” Lund says. “It was the same in Copenhagen. It’s like walking in the dark and someone turns on the light.”

The key to improving the acoustics of a concert hall lies in getting a better mix of ‘direct sound’ – which comes to your ear straight from the stage, and ‘reflected sound’ which travels to listeners via walls, the ceiling and other surfaces. Because reflected sound travels further, it reaches your ear a fraction of a second later. The reflections depend on the shape of the room and where you and the performers are sitting.

There is no such thing as a perfect concert hall, in part because ‘good acoustics’ depend on what’s being played. Gregorian chants sound best in rooms with long reverberation times that emulate the churches and cathedrals in which they were first sung. But rock music played in a church would create an almighty din, an aural soup of dominating reflected sound energy. Another variable is the preference of the listener. Some like to feel enveloped by the sound of an orchestra, carrying them away on a cloud of aural bliss. Others prefer the clarity of more direct soundwaves that enables, with studied concentration, the sound of each individual instrument to be heard.

The key to improving the acoustics of a concert hall lies in getting a better mix of ‘direct sound’ – which comes to your ear straight from the stage, and ‘reflected sound’ which travels to listeners via walls, the ceiling and other surfaces. Because reflected sound travels further, it reaches your ear a fraction of a second later. The reflections depend on the shape of the room and where you and the performers are sitting.

There is no such thing as a perfect concert hall, in part because ‘good acoustics’ depend on what’s being played. Gregorian chants sound best in rooms with long reverberation times that emulate the churches and cathedrals in which they were first sung. But rock music played in a church would create an almighty din, an aural soup of dominating reflected sound energy. Another variable is the preference of the listener. Some like to feel enveloped by the sound of an orchestra, carrying them away on a cloud of aural bliss. Others prefer the clarity of more direct soundwaves that enables, with studied concentration, the sound of each individual instrument to be heard.

It’s the reflections that make the sound in the recording sound so different. And a similar effect is at play in a concert hall. “Improving the acoustics is a matter of getting the right mix of direct sound and reflected sound, especially the first reflections,” says Lund. First reflections are the sound wave that bounce off a surface just once before they reach you ear. Sound waves that hit several surfaces before reaching you are known as reverberation.

The trick is getting the right amount of early reflected sound from the right directions without too much reverberation. Too many strong reflections confuse the brain's processors and you can’t figure out from where the noise is coming – or where the tiger is in the forest.

The problem of reverberation is exacerbated by the fact that direct sound waves tend to run out of puff (and hence can’t be as well heard at a distance) relative to reflected soundwaves. The level of reverberation tends to stay the same regardless of where you are in the hall – and if you’re seated up the back it can even overwhelm the direct sound and first reflections coming from the stage.

The changes to the Concert Hall are designed to do two main things – get sound back down to the orchestra so players can hear themselves and each other, and get more first reflections into the stalls and up into the circle. The results of the tests in late 2016 will be comprehensively studied before work on the Concert Hall begins in earnest in February 2020. The works are expected to take up to two years.

Feedback to the testing of the prototypes from players in the Sydney Symphony Orchestra has been encouraging. Chris Tingay, a clarinettist, said he could hear other parts of the orchestra better than ever before.

“It’s the biggest change I’ve had in 24 years of playing with the orchestra in this hall. I think the orchestra will improve as it learns to play with a new acoustic.

“It did occur to me that the really great orchestras in the world, they have really great halls. If you look at the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam or the Musikverein and the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra. They have amazing acoustics to play in. I wonder whether the better the hall, the better the orchestra.”

For Lund, who’s refined his knowledge of acoustics from years of experience, what he wants audiences to feel when the Concert Hall reopens is very easy to explain.

“During the rehearsal I spent a lot of time moving around different seats. I was in 30 different positions around the hall, through all four concerts with Tchaikovsky and Mozart. And I think it was the second concert when I leaned back and just enjoyed it. That’s what I would like people to do. I want people to sit back and think wow, it really sounds good. The quality of the acoustics won’t be for a specialist to hear. It will be for anyone to hear that they’re really improved.”

How to make a hall sound better

Process

The process for improving acoustic begins, logically enough, with the ear. Jürgen Reinhold and Gunter Engel have listened to concerts and also interviewed performers, conductors and regular listeners about their perceptions of the sound. Then models of the Concert Hall are made – both digital and physical – and how sound moves around is mapped.

Reflectors are then added to the models – their shape, number and location is fiddled with to get the desired result. Then prototypes are built and tested in the actual hall. Physical tests are critical.

“With the higher frequencies the computer is fine at simulating,” says Gunter. “But when it comes into this intermediate region it’s very complicated. There are no close theoretical models to predict how the sound will travel. There are a lot of assumptions. So you need to visit the hall and test.”

Testing

Testing initially involves using lasers to measure where light goes when it travels from the stage and bounces off the reflectors. Sound waves are far more diffused than the light of a laser, but the laser provides a starting point that can be modelled by a computer.

Then a device which looks like a yellow and black soccer ball on a tripod is set up. Its 12 speakers emit a long ‘whooping’ sounds which starts at the bottom of the range the human ear can move and gradually moves to the very highest. The sound waves are recorded, measured and tracked against the model made of the hall so that different reverberations can be tracked to different surfaces.

“Acoustics is easy,” Reinhold says with a laugh.