My Inspirational Teacher: Emily Flannery

First Nations dancer Emily Flannery on her mentor Uncle Dujon, the Cultural Tutor who gave her the courage to "stop holding herself back"

"She really made us care, and we knew that she cared about us" – that's what Grammy Award-winning singer Adele said about her high school English teacher Ms McDonald, who she hadn't seen for twenty years, before an on-stage surprise.

We all have that one teacher who saw our potential, who pushed us that little bit harder to be all that we could be. My Inspirational Teacher is a new Opera House series where we ask artists and educators about the people who untapped their potential. Whether a teacher, tutor, coach, Auntie or Uncle, these are the stories of the ones who made us care... while caring about us.

First up, Emily Flannery, the Wiradjuri performer and choreographer behind the upcoming contemporary Indigenous dance work Bulnuruwanha (Taking Flight), which will premiere in the Centre for Creativity in 2022.

Perched atop a hill on Darkinjung land in the Central North Coast, surrounded by Mt Penang parklands with a majestic fire pit for Welcome to County ceremonies marking the entry, is the National Aboriginal Islander Skills Development Association (NAISDA), Australia’s premier Indigenous training college. It’s a place of learning and deep cultural connection where proud Wiradjuri woman Emily Flannery had her dance practice and sense of belonging completely transformed.

For emerging Indigenous dancer and choreographer Emily Flannery, the age of 20 brought a diagnosis of Achilles Tendonitis. After years of classical ballet training, she found herself at a crossroads. Acting on a fleeting thought that her dance career might be over, Flannery decided to pursue studies in Psychology and Sociology. However, it quickly became evident that after lifelong education through movement, the rigorous desk hours of her chosen field of study weren’t conducive to her visual learning preferences.

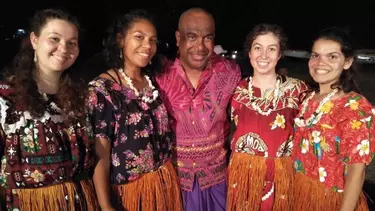

Unbeknownst to Flannery, her sister Amy had simultaneously submitted an application for the pair to enrol in the Developing Artists program at NAISDA. For their audition piece, the Flannery sisters learned choreography by NAISDA Cultural Tutor Dujon Niue (Uncle Dujon). A NAISDA graduate and Artistic Director of cultural dance group ARPAKA, Uncle Dujon’s arrangement was Flannery’s first encounter with the dynamism of cultural dance and the start of a professional relationship that would greatly impact her career.

Flannery explains that most cultural dancers start young, “so learning as an adult, it’s not in your body the same way”. Despite her lifelong experience of learning through movement, Flannery found that Uncle Dujon’s pieces included so much more than choreography. Dancers were required to sing and dance simultaneously and due to Uncle Dujon’s Torres Strait Islander heritage, the singing was done in the language of the Western Islands (Kaiwalgau) and the Eastern Islands (Meriam Mir/Miriam Mer).

With a “huge smile and little round belly” Uncle Dujon guided Flannery through two years of multidisciplinary study. When considering why Uncle Dujon was so revelatory to Flannery, she speaks frequently of his generosity of time, knowledge and culture.

“Particularly with ballet, a lot of it was based on aesthetics and so privilege was given to certain people over others. I found that with him, it was the time spent that was the most important thing. Sometimes we wouldn't talk, we would just sit together and make props or paintings.”

“But that is also how culture is passed on and transferred and shared. So you don't even realise that you're learning and you don't even realise that you're part of something that's so much bigger than you. But you're also keeping traditions going without even really knowing – it’s kind of magic”.

During his time as her Cultural Tutor, Uncle Dujon took the class to his hometown of Moa Island to finesse their skills in Torres Strait dance, a memory Flannery holds dear. The extensive time together shed a light on his creative process as an artist, “he would dream about his songs that he was creating and trust that he had it all within himself”. In comparison to the rigidity of classical ballet, Flannery was astounded by the constant evolution of Indigenous dance and the creativity this provided to its practitioners. Uncle Dujon imparted a sense of flexibility when it came to creativity, which is now a prominent fixture in Flannery’s own process.

It was his belief and generosity that helped me believe in myself more and go back to my mob and not be self-conscious.

During the most recent lockdown, Flannery was working at the Art House, Wyong and cleaning the theatre while she received JobKeeper. Simultaneously, she was also in the first stage of creative development for her upcoming work Bulnuruwanha, when it dawned on Flannery how much Uncle Dujon influenced her process. Ordinarily, she would be diligent about her performance hours, but faced with the mundanity of cleaning, she seized the opportunity to daydream.

“The next day, we created four or five minutes of one of the sections and I probably never would have done this [without experiencing Uncle Dujon’s creative process]”. Flannery realised, “maybe this is my process, like maybe daydreaming is how work is created”.

As Flannery reflects on the impact of Uncle Dujon on her dance practice, it becomes evident that his impact had much greater reach than the mirrored walls of the NAISDA studios and the cultural immersion trip in Moa Island.

“For a lot of Aboriginal people, we can be quite self-conscious about the colour of our skin because of colonisation. You know, we all look different now from how we did 100 years ago. But he would say, ‘you know who you are’ and everyone got treated the same.”

“It was his belief and generosity that helped me believe in myself more and go back to my mob and not be self-conscious. Being with him, and how welcoming he was, gave me courage to stop holding myself back.”