The French songwriting duo who dared to dream a dream

Many twists of fate led to this mesmerising concert celebrating the enduring music of Les Misérables, Miss Saigon and more

Alain Boublil will never forget the moment he and Miss Saigon producer Cameron Mackintosh sat in a gigantic helicopter sweeping across Sydney Harbour, the Opera House dwarfed below them, to announce the arrival of the show in 1995. “That’s when we developed an incredible story with Australia,” he recalls. “It was like recreating the iconic scene from the musical.”

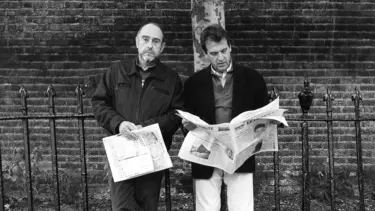

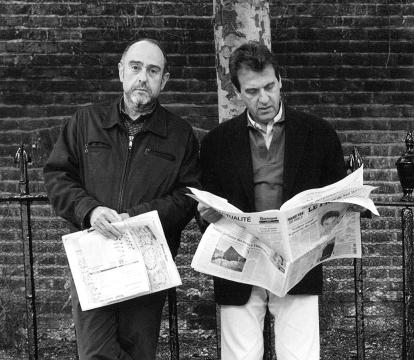

A moment to remember forever, it remains a highlight of the 40-year-plus collaboration of Alain Boublil and Claude-Michel Schönberg, the musical theatre masterminds responsible for transforming Giacomo Puccini’s soaring opera Madame Butterfly and Victor Hugo’s literary masterpiece Les Misérables into rock operas for the ages.

These astonishing works are celebrated in Do You Hear The People Sing?, as are their later musicals Martin Guerre, The Pirate Queen and even their first work together, La Révolution Française. A glorious night in the Opera House’s Concert Hall featuring the stars who have made this memorable music their own including Michael Ball OBE, John Owen-Jones, Rachel Tucker, Bobby Fox and Sooha Kim. It is the perfect tribute. Boublil and Schönberg were brought together by a song, after all.

It is the music of a people

Tunisian-born Boublil had grown weary of writing three-minute pop songs on the side of his day job working for a music publishing company. Yearning to reach higher, fate first stepped into his path as he flicked on his car radio one fine day in 1968 and heard ‘Tous Les Jours a Quatre Heures’ (Every Day at Four O’Clock) as performed by Patricia. Intrigued, he called the station to enquire who wrote it, bringing him to Schönberg’s door. A magnificent partnership was born.

“We were talking about doing something a little bigger than a song,” Schönberg recalls, “because, frankly, one day you are completely fed up having to come up with one verse, one chorus, one verse, change of key, chorus. And it goes on.”

But the seed that would one day grow into Les Misérables was still a long way from sprouting roots. There was no tradition of musical theatre in France when Boublil first fell under the spell of the form. His family moved to Paris when he was 18 years old, and he vaguely recalls seeing touring productions of Hair and Godspell. But it was West Side Story that truly dazzled him. “That changed my life,” he recalls. “It was a kind of epiphany that changed my comprehension of what music was. There was nothing like it in France, certainly not written by French people. And so it was a bit revolutionary, if I can say?”

Boublil feared the complexity of the 1957 musical that marked lyricist Stephen Sondheim’s Broadway debut was beyond him, until another fateful moment struck like lightning across the Atlantic. He caught Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice’s spectacular Jesus Christ Superstar on a trip to New York City in 1972. “And then I thought, ‘Oh my god. This I think I can do’.”

Spilling out onto the hubbub of 42nd Street, “long before it became a Disney paradise,” Boublil felt the flame sparked by West Side Story rekindling in his heart. Grasping, at last, the shape of a grand rock opera that would champion the heroes of the French Revolution, he could not wait to share his vision with Schönberg.

The colour of the world is changing

Taking as their lead The Who’s Tommy, the pair set about writing their symphonic double album La Révolution Française. Much to their surprise, it was an instant hit when released in 1973. They were fielding calls from television stations that wanted visuals, prompting a makeshift shoot in which friends donned period attire sourced from costume departments. Calls to stage it as a concert followed.

Debuting at the Palais des Sports that same year, Schönberg, a gifted singer, took on the fateful role of Louis XVI. “I was decapitated 45 times,” he laughs, “and each time the guillotine came down, the crowd were cheering and there was a standing ovation.”

History then took its sweet time. “After the overnight success of La Révolution Française, nothing happened for us,” Boublil chuckles. “We went back to our offices, but the passion became an obsession.”

So much so that the day jobs had to go after another fateful trip, this time to London, where Boublil would catch producer Cameron Mackintosh’s revival of Oliver! Street urchin the Artful Dodger conjured up the image of Gavroche. “It was like a cacophony in my head,” he recalls. “I was watching Oliver! with one half of my head, and the other was already imagining Jean Valjean, Javert, Fantine, Marius and Éponine.”

It’s a tradition for Cameron to have lunch for the whole creative team the day after opening, but it was something more like a funeral.

Les Misérables as we know it was born. Opening at the Palais des Sports again, they had another massive hit on their hands. But a fateful call from Mackintosh would take it to the world. Bringing Boublil and Schönberg to London, they set about reworking the musical in English, aided by lyricist Herbert Kretzmer, and for audiences less familiar with French history.

Opening at the Barbican Centre in 1985, Schönberg recalls it was greeted by “catastrophic” reviews. “It’s a tradition for Cameron to have lunch for the whole creative team the day after opening, but it was something more like a funeral,” he recalls.

If critics turned up their noses, then audiences took no notice. Flocking to the show in droves, it has hardly left stages worldwide since, and is the longest-running musical in London’s West End.

True love never has to end

Schönberg had long nursed a desire to rework Madame Butterfly, but he couldn’t quite grasp the framework. Until one day, he flipped open a magazine and was startled by a photograph of a Vietnamese mother handing over her young daughter to American soldiers at Tan Son Nhut Air Base during the Fall of Saigon at the close of the Vietnam War.

This impossible sacrifice struck him like lightning, inspiring the doomed love affair between US Marine Chris and South Vietnamese bargirl Kim. Boublil knew his partner was onto something. “I was bowled over by that story of the misunderstanding between two people, which, in fact, is a misunderstanding between two countries.”

The weight of history hangs heavy over these musicals, perhaps explaining why these epics have burned into the collective consciousness, particularly as the terrible spectre of war looms larger.