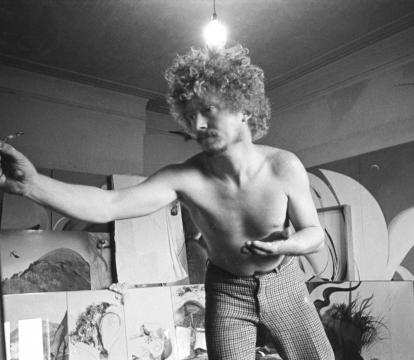

Brett Whiteley in the Green Room

Brett Whiteley (1939-1992) remains one of Australia’s most distinctive creative forces.

Brett Whiteley

Born in Sydney in 1939, Brett Whiteley remains one of Australia’s best known and most eagerly collected artists. He left Australia in 1959 after winning an Italian Government art scholarship, immersing himself in Italy and France before moving to London, where he quickly caught the eye of influential curators. He took part in several individual and group exhibitions while becoming the youngest artist to have work purchased by the Tate. Later in the decade he moved to New York, then Fiji, before returning with his wife Wendy and daughter Arkie to Sydney in 1969. From then he based himself in Lavender Bay, on Sydney’s lower north shore, and established himself as one of the country’s most dynamic artists. He explored his battles with addiction in his art and twice won the Archibald prize. He combined his 1978 win with the Wynne and Sulman prize, the first artist to win all three honours. He died in Thirroul, on the NSW south coast, in 1992, aged 53, and his studio in Surry Hills continues to celebrate his legacy to this day.

Aina Reega, by Brett Whiteley

By the curve of the line, by the sweep of the curls that dance across the page, the hand of the artist reveals itself with gentle, unambiguous clarity. In March 1991, the date of this picture, many Australians were familiar with Brett Whiteley, both for his art and his life. There he was, studying the curves of his wife. Or there, the bowerbird facing up to creativity and addiction. Or there, looking out from his home in Lavender Bay, on the northern edge of Sydney Harbour, painting the activity in the water, the ferries, the boats, the birds, as well as the performing arts centre on Bennelong Point that was coming to life before his eyes.

Robert Hughes, the art critic, identified this talent early on: “No Australian painter possesses, so far as I am aware, Whiteley’s precocious instinct for making marks on surfaces, the magical procedure of good drawing which turns a blank sheet of paper into a live space by the pull of two scribbles in opposite corners.’’

As a draughtsman, Whiteley was blessed with an economy of style. He needed only a few lines to bring about a sense of motion and sensuality. He worked quickly, pouncing on the page with a lightness of touch, a falcon in flight. In this way, subject and object were moving together: he was a ball of energy, restless, never sitting still.

The act of drawing meant grasping at the tide: “Drawing is a completely unrehearsable and unrepeatable visual truth,” he said. “The purpose of drawing is to make freshness permanent – to trigger astonishment. Out of billions of moments of futility a few seconds of rightness are immutably held forever.”

Is it any wonder, then, that so many of Whiteley’s most affecting pictures are powered by the act of movement itself? In the mid-60s, while living in London, he produced two separate but connected series: one, based on animals in the London Zoo; the other, on John Christie, the serial killer whose frenzied crimes had taken place in the neighbourhood where Whiteley lived. Later, while travelling in India, he drew a portrait of Ravi Shankar, the sitar master a blur in the midst of performance. Later still, upon his return to Sydney, he needed only a dash of white to convey the wash of the passing boats in the harbour below his home.

Here, Whiteley dedicates his picture to Aina Reega, the dancer and teacher who “lived her whole life for the dance”. Reega came to Australia after World War II, by way of Latvia, soon joining the Borovansky Ballet, a precursor to Australia’s national ballet company. Before the Borovansky, she performed around the country with her husband, Arvids Fibigs, both former dancers with the National Grand Opera in Riga (now the Latvian National Opera and Ballet).

They also danced with local folk dance groups and with an Australian company called the National Theatre Ballet Company, for which Reega danced the role of the Bird in Peter and the Wolf. In 1954, she danced at a Royal Gala for Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip at the Empire Theatre in Sydney, the first gala performance for a reigning monarch in Australia. The work was Corroboree, choreographed by Beth Dean to the music of John Anthill, and a regional tour followed the royal performance.

But what connects Aina Reega to Brett Whiteley, given he was just a teenager at the time of that Royal Gala? A clue comes from the artist's ex-wife, Wendy. She recalls Reega being introduced to Brett by Rosina Tedeschi, who taught him Italian in the late 1950s. The meeting appears to have stayed with him. Whiteley wrote his dedication just five months after Reega’s passing in October 1990 – and the dancing lines on his picture echo the words of a critic in The West Australian, back in 1953, about a performance by Reega and Fibigs:

“There is a kind of flashing elegant certainty in their execution of figures, movements, designs. Other virtues too, as called for, but in all moods and varieties a command of style which is a keen pleasure for the beholder.”

Whiteley was 52 when he completed this picture, with little less than a year to live. Recently separated from Wendy, he was unsettled, out of sorts, but continuing to produce work at a rapid pace. He was also enjoying growing public appreciation, including an Order of Australia and strong interest from collectors, even if some critical voices were finding fault with his newest work.

A few months earlier, he had given an interview to Andrew Olle on 2BL radio in which he reflected on challenges both personal and creative. At one point, he used the language of Narcotics Anonymous to describe the “higher power” that governs the pursuit of art. He was talking about being a vessel for ideas, and it’s an observation common to many artists as they interrogate the ecstasy and mystery of their work – an interrogation, like a dance, that never quite fixes itself in place.

“The closer that I could adhere to that,” he said, “I am sure that the more definite and extraordinary my art would get because I am the telegram boy rather than the mighty mouse.”

Ashleigh Wilson