Judy Cassab in the Joan Sutherland Theatre

Judy Cassab, born in Vienna in 1920, migrated after the war to Sydney, where she became an artist of singular talent and vision.

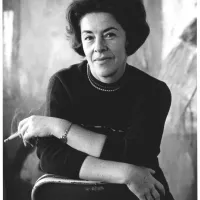

Judy Cassab

Judy Cassab was one of the country's most formidable artists and most in-demand portrait painters. She won the Archibald Prize twice, the first woman to do so, among many other prizes and honours. Cassab was born in Vienna in 1920, the daughter of Jewish Hungarian parents. She survived World War II by concealing her identity, though most of her family were killed by the Nazis. She later migrated with her husband and their two sons to Sydney, where she continued to develop as an artist of singular talent and vision.

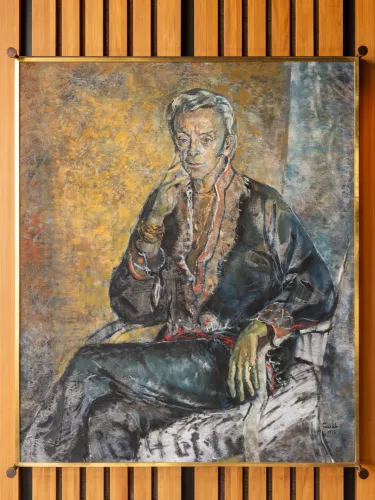

Dame Joan Sutherland, by Judy Cassab

Southern Foyer, Joan Sutherland Theatre

“Sydney is beautiful. A thousand bays and a thousand hills and a thousand ships and the end of the world.”

So wrote Judy Cassab in January 1958 upon returning to Australia from America. While overseas, she had been busy, the recipient of more commissions than she could accept, but she missed her family too. She also missed her adopted home, a city that held her imagination even if it seemed far removed from the energies of the world at large and even further removed from the turmoil of her younger life.

Cassab, or Judit Kaszab, was born in Vienna in 1920, the daughter of Jewish Hungarian parents. After the horrors of World War II, she arrived in Sydney in 1951, travelling from Hungary with her husband, Jansci Kampfner, and their two children. Their immediate families died in Nazi concentration camps; Cassab survived the war by posing as a family’s Catholic maid.

Once in Sydney, she developed a reputation as one of the country's most formidable artists and most in-demand portrait painters. She won the Archibald Prize twice, the first woman to do so, among many other prizes and honours.

In October 1973, she found herself in the company of some 2500 people at the opening of the new Sydney Opera House. In her diaries – a remarkable account of post-war creativity – she describes the spectacle she witnessed on the day, with tugboats pulling giant pink ribbons away from the sails and thousands of pigeons and coloured balloons rising to the sky.

“The night was positively the most glamorous I have ever seen,” she writes. “Premiers of each state, the famous, the titles, the rich, seated strictly by protocol."

Three years later the Sydney Opera House Trust commissioned Cassab to paint two portraits for the new building: one of the coloratura soprano Joan Sutherland, the other of dancer/director/choreographer Sir Robert Helpmann. Cassab had no shortage of commissions – “I am churning out portraits,” she wrote. “I feel like a dentist. Next please. It’s not an easy way to make money” – but this felt different. She knew Helpmann already, and had painted him before, but the encounter with La Stupenda was an opportunity to engage with another performer, and one who was at the peak of her powers.

In July, Cassab made her way to Bennelong Point to watch a dress rehearsal of Lakme, the Delibes opera, with Sutherland in the title role for the Australian Opera. During rehearsal, the singer was wearing the dress she had chosen for the portrait. Cassab describes she scene: “The auditorium is buzzing with a television crew. I hold the sketchbook. I draw in the darkness, write down Prussian blue and emerald, for background; alizarin, brown madder and rose d’or for the dress. The director, interrupting La Stupenda several times. We meet in her dressing room, discuss sittings.”

The first sitting took place in early August. The atmosphere was relaxed and light, conducive to creative exchange. Cassab described her subject as a “delight”, noting that she could be hearing humming throughout the sitting: “The world’s best soprano sat humming a private concert for me.”

Ashleigh Wilson

Robert Helpmann, by Judy Cassab

Southern Foyer, Joan Sutherland Theatre

For decades, Sir Robert Helpmann embodied the art of live performance in Australia. He was the monarch of the stage: dancer, artistic director, choreographer, actor. His reputation was such that Judy Cassab, who painted his portrait on multiple occasions, considered him a worthy candidate to run the nation's new and as-yet unfinished performing arts centre on the edge of Sydney Harbour.

In 1963, during a trip to London, she visited the Royal Academy with Helpmann to see her recent portrait of him. She later recorded her thoughts in her diary: “Helpmann, I think, would love to become the director of the Sydney Opera House. Not only does he want to import the famous from overseas, but he wants to bring up a new generation of Australian performers. I can’t understand why they have not invited him to do just that.”

Cassab’s fancy never came to pass. The first general manager of the Opera House was Frank Barnes, though Helpmann was a frequent, enthusiastic guest inside the new building, as performer, director, producer and audience member.

Cassab was born in Vienna in 1920, the daughter of Jewish Hungarian parents. She survived World War II by concealing her identity, though most of her family were killed by the Nazis. She later migrated with her husband and their two sons to Sydney, where she continued to develop as an artist of singular talent and vision. The artist and critic Elwyn Lynn said she “went beyond the common, camera-like representations expected of portraits and revealed both the likeness and essential character of each sitter in a way that set her work apart from others”. Or as John McDonald put it in the Sydney Morning Herald: “Judy was one of the stars of a generation of post-war emigrés who did much to educate local sensibilities, giving Sydney a taste of European sophistication.”

Cassab was a widely admired portrait painter in her adopted country. She won the Archibald Prize twice, the first woman to do so, and such was the demand for her services that she struggled to keep up with demand. In March 1976, she was commissioned by the Sydney Opera House Trust to paint two portraits, of Helpmann and opera star Joan Sutherland, to be hung in the building.

Helpmann’s portrait was unveiled six months later – in Helpmann’s presence. It’s a picture of languorous grace and dignity. Its muted tones contrast with the flash of colour that lines his shirt, the flamboyant face of the arts in Australia.

At the time, Leslie Walford, a society columnist for the Sydney Morning Herald, was full of praise for Cassab’s achievement, calling it a “magnificent portrait” that captured Helpmann’s “vibration” perfectly. “His career is long and colourful, his face certainly one of the most known, his wit wasp-like, his spirit bright. None more qualified, therefore, than he to be immortalised in portrait form and to be hung in the Opera House.”

The painting was also used as the cover for Elizabeth Salter’s 1978 biography, Helpmann, which concluded with these words from its subject: “Theatre remains the only thing I understand ... It is the life I love.”

Ashleigh Wilson