Little Country Syndrome

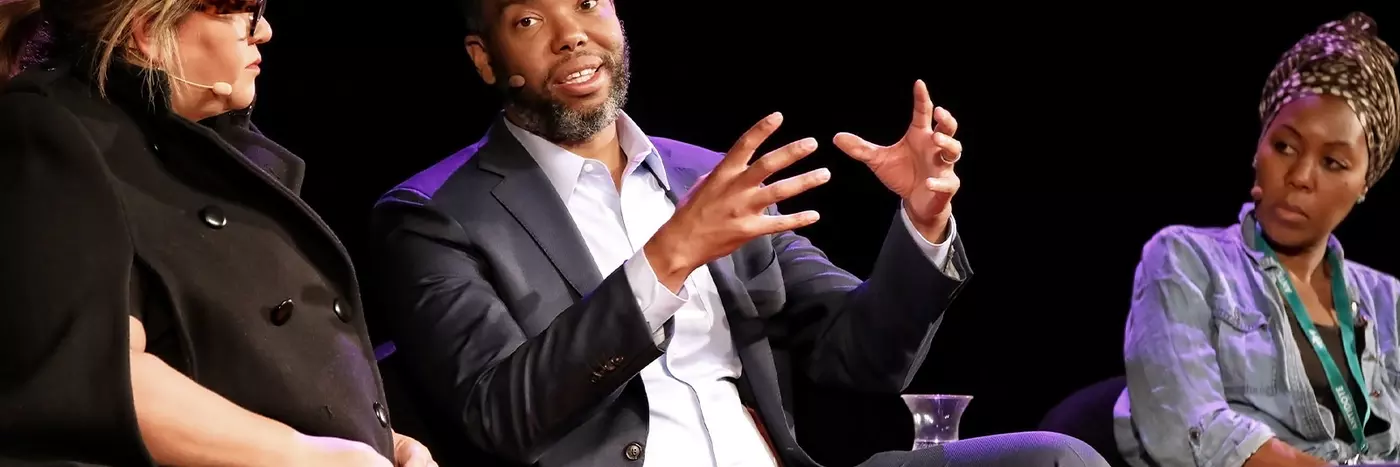

Why does Australia look abroad for solutions to our racial anxieties? For Antidote 2018, Nayuka Gorrie reflected on the work of Ta-Nehisi Coates

This article was originally published in 2018 in the lead up to Antidote festival.

Ta-Nehisi Coates has emerged in America, at least for the distant observer, as a voice of reason in the current political climate. There are a few factors that might contribute to this: he is an atheist, he was close to yet critical of Barack Obama and grew up in a slightly older generation than meme enthusiasts but is young enough to remain a part of the zeitgeist. When Donald Trump was elected much of the (white) world was shocked. Ta-Nehisi Coates was not. I recall an interview with Coates after Donald Trump was elected looking utterly resigned. I recognised this look; it was the look of someone who had accepted his fate to deal with those who have not accepted theirs. Even in his writing on Obama, he never gave in to unbridled positivity about the first black President. Underneath his writing was a current of critique. He was measured and sobering.

It is fitting that he is visiting us now. The last two weeks of August have demonstrated Australia’s ongoing problem with race. This is not hyperbolic. Around the anniversary of Antifa protester Heather Hyer’s death by white supremacists in Charlottesville, Sky News Australia hosted white supremacist Blair Cottrell. This was followed a few days later by Senator Fraser Anning’s maiden speech that even Pauline Hanson condemned. Shortly afterwards, politicians who outwardly disapproved of Anning voted in favour of keeping brown people locked away at Nauru and Manus Island. Reports then emerged that the children living on these islands are so traumatised they have been self-harming. And there were two leadership spills. One contender, Peter Dutton, has said that allowing Lebanese immigration was a mistake, that people in Melbourne fear going to restaurants at night. The other contender, Scott Morrison, established that this was referring to the weird obsession the Victorian media and politicians have with non-existent African gang violence leading up to their state election. Alan Jones said the ‘n word’ on air. All in just two weeks.

...we look to writers of colour to help us make sense of the world.

In times of such political unrest we seek guidance. In Australia, we commonly look to other countries. Particularly when it comes to matters of race and identity, we look to writers of colour to help us make sense of the world. During her visit to Australia last year, Reni Eddo-Lodge commented that she was in demand for speaking engagements in Australia, but less so in America because the market for commentary on race politics is saturated there. In Australia, turns out, it is not. Part of this, I believe is our cultural cringe; the lack of commercial success for homegrown cultural outputs such as Australian film tells me that we aren’t prepared to back something unless its recognised internationally first. The women of colour in Hot Brown Honey, whose multidisciplinary performance art deftly tackles intersectional feminism, have found themselves on the cover of Vogue UK, yet this level of acclaim has eluded them in Australia. This cultural cringe means we don’t listen to what people – black people – from here have to say about race. Cornel West has visited twice in the last three years selling out shows around the country and appearing on Q&A each time.

Australia suffers from what could be called 'little country syndrome'. Since World War Two we typically turn to the US for political guidance. This is all very obvious from a country whose white population came about as a result of a penal colony constantly turning to and rushing to the aid of the mother country in its early war efforts (see: the Boer War and World War One). America’s cultural imperialism means we are exposed to so much of their cultural and political output. A huge consequence of this has been formulating an understanding of race through an American lens. Australia’s concept of Blackness is formed by what we have observed from them. We know more about Martin Luther King than we do about Uncle William Cooper.

Black writers do not exist to soothe the anxiety of good white people.

Despite all of the above, I do get excited when internationally recognised black people like Coates visit Australia and echo what we already know to be true. I can feel the excitement of small ‘L’ liberals. I am one of them. “Save us from our own stupidity”, I can hear them saying. “Tell us how to live!” It’s natural that we expect comfort from writers, especially those like Coates who bring what is in shadows to light. It’s easy to place expectations on a visiting writer whose body of work offers a reasonable take on current affairs. I hope those who go to see Ta-Nehisi’s events at Antidote go beyond wanting their racial anxiety soothed. Black writers do not exist to soothe the anxiety of good white people. Australia needs to do the work but this labour does not fall on black people.