A tribute from Barry Pearce

I’m sorry not to be Barry Humphries standing before you, certain that he would have liked nothing more than wax lyrical – with a few wicked barbs of humour, no doubt - about his friend John Olsen.

When Olsen’s son Tim rang me last Monday morning, lamenting the passing of Barry so soon after his father, he said jokingly I was the next named Barry in the queue to speak today. But I must say if we were talking about cars I would have to be classified as an entry level Holden compared to a Porsche, or Maserati perhaps.

And so I guess this eulogy in some ways has to make reference to two colossi of Australian culture.

Barry Humphries and I crossed paths occasionally, but I was never really part of his landscape. I found his fierce intelligence rather scary to be honest. Although there was one memorable encounter at Margaret Olley’s house in Paddington.

I turned up to see her and there he was in the big room where she worked. And he wasn’t scary at all, talking politely as if tamed by the studio of a painter he admired. We touched on a number of artists during which I brought up the name of Olsen. Barry said straight, like bowling me a googly: “Tell me, what do you think of John’s Five Bells mural in the Opera House?” Suddenly, it was scary, like being in the witness box.

I said carefully that I thought, given the difficulty of the challenge of scale and context of Utzon’s architecture, the overwhelming presence of a vast adjacent purple carpet, and the mockery Olsen received from workmen still on site, he managed to resolve it incredibly well.

Then, trying to avoid a debate, I added that the mood of the mural actually reminded me of how the French writer Stendhal claimed Mozart’s music to be a tide-like invasion of the soul.

“Ah yes,” said Barry, “a kind of adagio, I suppose, in musical terminology, the slow hallucination of Joe Lynch drowning in a watery heaven according to Slessor’s poem.”

“Well,” I replied, “I thought of it more as a dreamlike vision of death transformed, as in Dylan Thomas’s Under Milkwood.”

“Of course,” he said, “and what did Stendhal say about Beethoven?” “Don’t know,” I replied, “I am only aware the German poet Goethe declared Beethoven’s personality was completely out of control.”

At this point Margaret chimed in, coming back with a glass of water and, not listening properly but familiar with musical terms, exclaimed loudly: “What do you mean adagio?. More like agitato surely where Olsen is concerned, always on the move! Agitato!”

She got the wrong end of the stick but wouldn’t let up, until Barry, who loved John, took off his hat and broke into song, something like:

I say adagio and you say agitato. You say agitato I say adagio. Adagio, agitato, adagio, agitato…let’s call the whole thing off!

At which Margaret burst out laughing and the tension was broken.

Of course you know Barry wanted to be part of the give and take of painter’s talk, especially when it related to Olsen. It was his fantasy to be recognised as a fellow artist, or a sort of manquer participant.

In fact he and Olsen painted together on occasion, when Barry eventually discovered his place within the challenge of being a brother of the brush.

Olsen recounted a story at Lucio’s in Paddington during one of our monthly lunches of kindred spirits. It was about a trip with Barry and John arranged by David Dridan, South Australian painter, in 2015. They travelled to the Coorong, and up the Murray River including Renmark and Mildura.

All three artists were octogenarians, so of course there was to be no sleeping in sleeping bags on the ground. They had comfortable beds and ate well at nice cafes and talked through the night. And in one instance, when the group was working at the bottom of a shallow hill with their stools and easels Barry moved up a little higher as if to avoid David and John looking at his work, declaring “I am a symbolist!”

A little later he mover further up still at work saying “I am an impressionist!” After another period, moving even further away he finally blurted loudly, arms akimbo with faux tragic expression “I’m a failure!”

But if Barry’s eyebrow cocked at Goethe’s comment about Beethoven being applicable to him, a personality out of control, it certainly wasn’t so for Olsen, who had a radar of stability beneath any sense of tumult and chaos.

Yes even in spite of an excessive appetite for sex, food, friendships, travels within and beyond Australia, and the riotous joie de vivre of his pictorial language. In other words, an enthusiastic bacchanalian, but always in control, always knowing exactly what he was doing following his muse in the serious game of painting and drawing.

Indeed when you meditate very carefully upon his paintings you may detect, beyond lines and shapes meandering towards the edges or slicing each other flirting eloquently with a prospect of collision, a certain classical calculus that holds the gaze.

I think he developed this sensibility partly through his extraordinary grasp of literature. Poetry, biographies, novels, histories, art theory: you name it, he would have read it. And his power of retention was formidable.

At one of our recent lunches at Lucio’s, I asked him what he was reading. He replied he was on his second journey through Shakespeare’s sonnets and quoted some by heart. “They must be read in one’s maturity. The whole human condition is there in one package. Everything,” he claimed.

And John was exceedingly generous as well as brutally honest in his appreciation of artists past and present, Indigenous or non-Indigenous. I mean all artists have to be selfish I suppose but I never saw in him any overt sign of narcissism. As a Trustee of the AGNSW he actually encouraged me to come to Sydney in 1978 to take on a Whiteley retrospective when he and everyone thought Brett would die soon from his drug addiction. That didn’t happen as we know and the retrospective was delayed until Brett actually obliterated himself at Thirroul in 1992.

When I was preparing for the retrospective that followed, I told John I was struggling to rationalise the significance of drug addiction for Brett’s turbo-charged confidence. Now that was really scary. He responded calmly: “Well, you know Barry, just bear in mind genius does not know itself,” but could not remember the source of that quote. I tried everything to track it down, and later stumbled across it accidentally, leafing through a small book of letters by Keats. Twenty years on John suddenly out of the blue recalled that it was indeed Keats, thinking the poet may have inferred that genius could be a kind of sublime monster, simply doing what it had to do, leading talent by the nose rather than the other way round.

So this is just a small example of how much poets were as close to Olsen’s heart and intellect as painters, bound to him by a mysterious collective urge to reach some sort of mystical, or metaphysical zone of being.

One of his favourites was the late Irishman Seamus Heaney, and he loaned me Heaney’s memoir Stepping Stones. John had underlined one particular passage about how in every city Heaney visited on public reading tours he made sure to go to its major art museum and quietly meditate upon the greatest works to help steady his spiritual compass.

Needless to say, there are paintings with which you can do the same thing in major collections here. It’s all that really matters in the end, a solitary act of connection between you and a work of art far more important than the crowd-counting ethic beloved by politicians and money-counting bureaucrats. And you may as well start with an Olsen painting, almost any Olsen painting. Interestingly, although he would never reject the benefits of fame, John felt basically that mass popularity was very over-rated.

Speaking of solitary souls, one lovely poet John invited to our regular lunches at Lucio’s was his old friend Robert Gray.

Robert had produced a memoir called The Land I Came Through Last, a title borrowed from Christopher Brennan; and there was an anthology, Cumulus, including a magnificent portrait poem which Robert dedicated to his artist friend. I’m surprised the newspapers didn’t crack on to this and publish the whole thing. It’s fabulous.

That poem is based on a visit to Olsen’s studio in the Blue Mountains and the discovery of a handful of goose quills on his workbench. John explained how he used the quills, cutting the ends into little nibs and gave one to Robert, encouraging him to use it.

On the way home in a chauffeur car, Robert placed the feather on the back seat beside him. Through windows opened as a relief from the heat, it was snatched into the air by the slipstream of a speeding truck, floating in a graceful arabesque until disappearing into the bush.

Thus the poem was not only an intimate observation about the ineffable mystique of Olsen’s drawing, but also symbolic of his inner-desire to become immersed and lost within the landscape he adored.

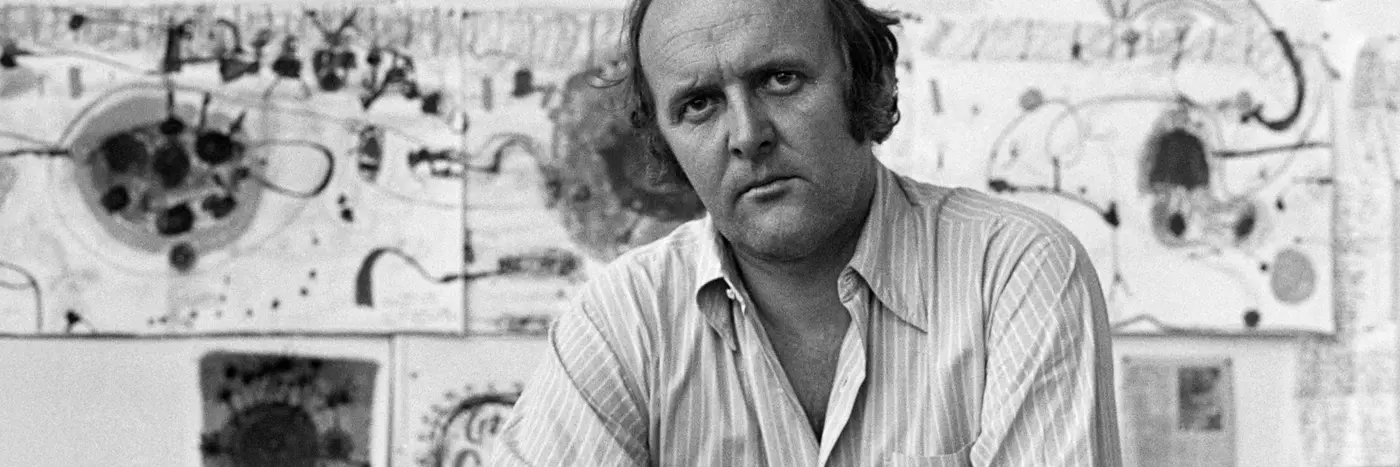

My favourite photograph of all time shows John in Clarendon, 1983, a town at the base of the Adelaide Hills where he briefly lived with his third wife Noela. He is shown leaning towards us over the edge one of his most beautiful, elegiac paintings laid flat, Golden Summer, Clarendon, having just brushed on a damar wax glaze to heighten its translucence. I was witness to that waxing and saw him mix it like an alchemist.

In the photo he stares affectionately at the painting as if it was a pause in time with a Gauguin-esque sense of Where am I going from here?, reminding us of Donde Voy?, the Spanish title that landed on a melancholic painting six years later at the completely opposite end of the tonal scale.

However in the sunny utopian epicentre of Clarendon in 1983, he is perhaps also reflecting upon his beginnings, growing up in Newcastle and Sydney, attending Julian Ashton’s Art School, travel and study in Spain and Europe, Spain in particular entering his DNA.

He may be thinking too about how by this time he had already pursued his muse in the rat-race of Sydney and her Harbour, then eventually across the entire continent, edge to edge with Lake Eyre in the middle, with enough breadth of experience to ask himself the question:

Who really owns this landscape? And wherein lies its truest ethos of responsibility? “In spite of terrible things that have happened,” he said, “in a purely poetic sense we should all own it together within a harmonious equilibrium rather than dispute it through division and resentment. That is the epic crusade we all face.”

And finally, poised on the edge of Golden Summer, Clarendon like a Scandinavian god from his ancestry, he seems in this photograph ready to dive down into it and fulfil the destiny inspired by Eliot’s words that he must find the moment where he finally becomes the landscape as the landscape becomes him.

Which brings us to his last painting currently hanging in the Wynne Prize, The Lake Recedes, where we may discover that the Holy Grail moment finally did arrive as John went to the other side; his palpable presence beckoning us to share his grand revelations and somehow accommodate the huge void left by his passing.

Vale John, our thoughts dwell on you and your family, in particular Tim and Louise, children of Valerie, and including those who have gone, each in their own way an essential part of the pain and joy of your journey, and a legacy never to be forgotten.

Barry Pearce is Emeritus Curator at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. This is an edited extract from his eulogy delivered at the Olsen Gallery in Sydney on April 27 2023.

Read more about John Olsen at the Sydney Opera House