Michael Nelson Jagamaraand Possum Dreaming

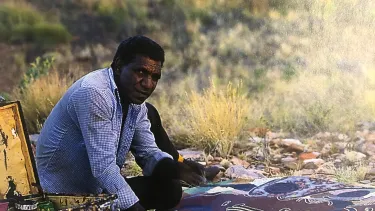

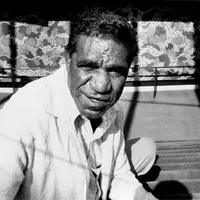

Jagamara’s artistic journey spans one of the most remarkable periods in Australian art, contributing to a creative movement that captivated audiences on an international scale. In Dreaming the Land: Aboriginal Art from Remote Australia, Dr Marie Geissler wrote that his parliamentary mosaic had exemplified the artist’s role “in driving forward reconciliation between black and white Australia.” For those fortunate enough to meet him, he embodied the qualities of the quintessential bush gentleman. Dressed in his jacket and distinctive Akubra hat, he exuded a dignified presence, often sharing humorous anecdotes and stories. Whether in Papunya or New York, Alice Springs or Brisbane, Sydney or Vienna, Jagamara often struck up conversations with new friends and passers-by alike, introducing himself with a warm smile and a handshake, announcing, “Hello, I’m a famous artist!”

Michael Nelson Jagamara

Born in Pikilyi, a remote Northern Territory outstation, in 1946, Michael Nelson Jagamara spent the early part of his life at Yuendumu, a larger community about 290km northwest of Alice Springs. He embarked on his painting journey in the early 1980s in the Central Australia community of Papunya. As a second-wave artist in the internationally renowned Western Desert art movement, he depicted stories that had been passed down to him by his grandfather, Minjina Jakamarra, for Papunya Tula Artists. He maintained his shareholding in this company throughout his life. Much of Jagamara’s artistic focus centered on the Mt Singleton area, encompassing Dreaming narratives such as Kangaroo, Yam, Possum, Bush Turkey, Goanna, Flying Ant, Rainbow Serpent, Rain and Lightning. In 1993, five years after his 196-metre mosaic was installed in the forecourt of the new Parliament House in Canberra, he was honoured with an Order of Australia medal for services to Aboriginal art.

As Vivien Johnson recounted in her comprehensive monograph on the artist, Jagamara left school in Yuendumu at 13 after his initiation into Warlpiri law. He travelled north, droving cattle, shooting buffaloes on the Alligator Rivers, and spent a short time in the army before heading back to Warlpiri country and settling in Papunya. “Seeing him operate with effortless command of the English language and Western cultural mores,” she wrote, “few realised that Jagamara’s life journey had begun ‘foot walking’ across his ancestral lands with his extended family.”

Possum Dreaming

In 1988, Jagamara’s monumental 10-metre painting Possum Dreaming was installed at the Opera House, in the Northern Foyer of the Joan Sutherland Theatre. This intricately crafted work references the Possum Love Story, an epic narrative he revisited in numerous major works throughout his career. This traditional Warlpiri narrative lends itself to an operatic setting, portraying a tale of forbidden love and retribution. Jagamara explained the Possum ancestors’ dire messages for those who transgressed traditional law. In this story, a young Possum man and woman fell in love, but their different skin groups prohibited their union and strict tribal laws and moiety responsibilities prevented such intermarriage. One fateful night, the young couple fled in defiance, pursued by angry Possum elders. Ultimately, the lovers were captured and faced a death sentence, a lesson to all who defied tribal protocols. In the painting we see the recurring “E” shape to represent the possum paw print, along with roundels as sacred sites and sinuous lines symbolising marks in the sand created by the dragging of their tails. These elements appear and disappear across the surface as the chase unfolds from day to night and from site to site, moving east to west. With its composed symmetry, the painting transports us to a timeless space, reminding audiences that such stories might continue forever.

This is an edited extract written by Michael Eather, the owner of Brisbane’s FireWorks gallery, who worked with Michael Jagamara for more than two decades.

Michael Nelson Jagamara

For those fortunate enough to meet him, he embodied the qualities of the quintessential bush gentleman. Dressed in his jacket and distinctive Akubra hat, he exuded a dignified presence, often sharing humorous anecdotes and stories. Whether in Papunya or New York, Alice Springs or Brisbane, Sydney or Vienna, Jagamara often struck up conversations with new friends and passers-by alike, introducing himself with a warm smile and a handshake, announcing, “Hello, I'm a famous artist!”

A Possum Story

Michael Jagamara was born into and reveled in a time of great change and opportunities. Following the end of World War II, abstract expressionism had arrived in the Australian art world and Sidney Nolan completed his Ned Kelly series. Also in that year, in the north part of Western Australia, in an amazingly unread, event, at least 800 Aboriginal pastoral workers walked off the job and began one of the longest industrial strikes in Australian history.

Gallery

of