Our storyThe spherical solution

As construction of the podium began in Sydney, Jørn Utzon AC and his team of architects back in Hallebaek explored how to build the Opera House’s shell-shaped roof. Between 1958 and 1962, the roof design for the Sydney Opera House evolved through various iterations as Utzon and his team pursued parabolic, ellipsoid and finally spherical geometry to derive the final form of the shells. The eventual realisation that the form of the Sydney Opera House's shells could be derived from the surface of a sphere marked a milestone in 20th century architecture.

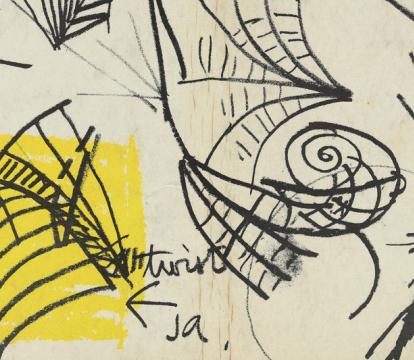

To work out how to build the shells, the engineers at Arup & Partners needed to express the shell shapes mathematically. Asked by the engineers in 1958 to define the curves of the roof, Utzon took a plastic ruler, bent it against a table and simply traced the curves. He sent these drawings to Arup & Partners in London, explaining these were the shapes he wanted.

The building’s shape slowly shifted away from Utzon’s competition drawings. His new curves were detailed in the Red Book, a complete set of plans, sections and elevations sent to the NSW Government in March 1958, which expanded on the schematic drawings from his competition entry. The roof’s ridge profiles had become higher and more pointed; the end shell form no longer cantilevered like a cliff over the sea. These higher profiles also allowed for more volume for the stage towers and auditoriums.

Yet the drawings contained in the Red Book were structurally unsound, with difficult bends near the roof’s footings. Each shell was different. The lack of a defining geometry would make it impossible for the builders to reuse formwork and would add to the building’s costs.

As the years and iterations continued without a satisfactory solution, resolution of the issue went from pressing to critical. By late 1961, three years had passed since Utzon had bent his plastic ruler on a table and a solution to building the shells had still not been found.

Utzon was even asked by the NSW government whether he should consider another engineering firm – but the architect refused to look elsewhere, convinced his collaboration with Arup would yield the solution. In the end the solution would come from Utzon himself.

Various myths surround the discovery of the so-called Spherical Solution, the unified answer to the problems of buildable shells. The iconic sculptural form of the Sydney Opera House essentially relies on the form of these shells, so the importance of finding the best solution to the roof cannot be underestimated.

As one of the more popular myths has it, Utzon had a eureka moment while peeling an orange. While it’s true that the solution can be demonstrated in this way, it had in fact been architect Eero Saarinen who, over breakfast one morning years earlier, cut into a grapefruit to describe the thin shell structure of the roof of his TWA Building, and later used an orange to explain the shape of the shells to others.

By his own account, Utzon was alone one evening in his Hellebæk office with a number of the most intractable Sydney Opera House problems weighing heavily on his mind.

Utzon was stacking the shells of the large model to make space when he noticed how similar the shapes appeared to be. Previously, each shell had seemed distinct from the others. But now it struck him that as they were so similar, each could perhaps be derived from a single, constant form, such as the plane of a sphere.

The simplicity and ease of repetition was immediately appealing.

It would mean that the building's form could be prefabricated from a repetitive geometry. Not only that, but a uniform pattern could also be achieved for tiling the exterior surface. It would become the single, unifying discovery that allowed for the distinctive characteristics of Sydney Opera House to be finally realised, from the vaulted arches and timeless, sail-like silhouette of the Opera House to the exceptionally beautiful finish of the tiles.

For Utzon, this realisation was an epiphany. His assistants were stunned when he explained the idea and set out to provide drawings that would prove its validity.

By finding the parts of a sphere that best suited the existing shapes of the shells, each new form could be extracted. Furthermore, only one side of each profile was required as this would be mirrored to complete the arch.

The Spherical Solution would become the binding discovery that allowed for the unified and distinctive characteristics of the Sydney Opera House to be realised finally.

By any standard it was a beautiful solution to crucial problems: it elevated the architecture beyond a mere style – in this case that of shells – into a more permanent idea, one inherent in the universal geometry of the sphere. It was also a timeless expression of the fusion between design and engineering.

In January 1962 Utzon submitted his Yellow Book: 38 pages of plans, sections and elevations setting out the shells, details of the precast ribs and the tiling. Its cover showed the principles of the spherical geometry that would allow the Opera House to finally be realised.

The Sydney Tile

Utzon wanted the shells to contrast with the deep blue of Sydney Harbour and the clear blue of the Australian sky. The tiles needed to be gloss but not be so mirror-like to cause glare. Utzon found exactly what he wanted in Japan; ceramic bowls with a subtle coarseness caused by a granular texture in the clay.

Three years of work by Höganäs of Sweden produced the effect Utzon wanted in what became known as the Sydney Tile, 120mm square, made from clay with a small percentage of crushed stone.

The 4228 tile chevrons required to cover the shells were produced in a factory set up under the Monumental Steps. Tiles were placed face down in one of 26 chevron shaped beds each with a base shaped to match the curve of the roof. In total, there are 1,056,006 tiles on the roof.

In his Design Principles published in 2002, Jørn Utzon would remark that the tiles “were a major item in the building. It is important that such a large, white sculpture in the harbour setting catches and mirrors the sky with all its varied lights dawn to dusk, day to day, throughout the year.”