Our storyPeter Hall and the completion of the Opera House

Peter Hall was already one of Australia’s brightest young architects when he took up the daunting role of design architect to complete Sydney’s new Opera House.

Hall had been a scholarship student at Sydney's prestigious Cranbrook School before completing a combined architecture and arts degree at the University of Sydney. At the end of his studies he was awarded a generous travel scholarship that afforded him a year in Europe, during which time he had visited Jørn Utzon AC in Hellebæk.

On returning to Australia, Hall went to work for the NSW Government Architect Ted Farmer at the Department of Public Works, where he helped design the Goldstein College Dining Hall at the University of New South Wales, which was awarded the prestigious Sulman Medal.

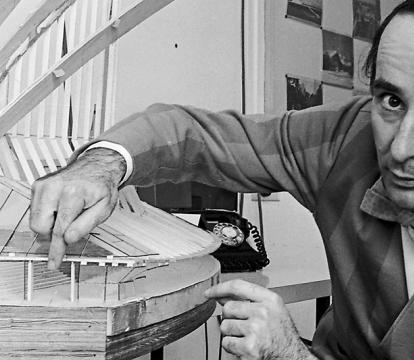

Peter Hall, 1966I’m overwhelmed but I think I can finish the Opera House.

Having resigned from the Department in early 1966 to pursue his own practice, Hall was approached by Farmer with the offer of the Opera House project. He initially declined, having previously lobbied in public for Utzon’s return. Asked again, however, he said he would be willing to accept the role on the condition that there was no possibility of Utzon returning. After speaking with Utzon by telephone, Hall accepted the position.

‘I'm overwhelmed but I think I can finish the Opera House,’ Hall said in an interview with The Daily Mirror. Even so, his appointment was too much for many of his fellow architects, who insisted that no one but Utzon should complete the Sydney Opera House.

With Utzon’s departure from the project confirmed, Hall and his partners – Lionel Todd and David Littlemore as part of a consortium known as Hall, Todd and Littlemore – worked through the requirements to establish a new brief for Stage Three of construction, which included the task of constructing and designing the interior and foyer spaces. Hall had been under the impression he would be following Utzon’s plans. It came as a shock to discover that the work required would be on a much larger scale.

Instead of the documentation they were expecting to find, all that Utzon had left were sketches and designs. There were no working drawings, nor were there the crucial drawings illustrating Utzon’s most recent thinking available to them. All were missing, along with about 5000 sketches and drawings that had been placed in storage by Utzon’s office assistant, Bill Wheatland, where they would remain, largely unseen, until 1972.

Hall spent the following months overseas visiting Utzon’s consultants, including engineers Ove Arup and Jack Zunz, acousticians Cremer and Gabler, and Willem Jordan, with whom he collaborated on the halls. He also visited various concert halls in Japan, Europe and the United States.

A year after Utzon and his family departed Australia, Hall received a letter that would lead, over the following months, to Hall and others exploring the possibility of Utzon’s return to collaborate with the government-appointed committee of architects.

Utzon insisted that Hall keep their conversations away from engineers Povl Ahm and Ove Arup, and friends and associates of Utzon. Hall noted that Utzon felt he could not trust Stan Haviland of the Sydney Opera House Executive Committee and that he was no friend of the Minister for Public Works, Davis Hughes, who had all but overtly engineered Utzon's departure from the project.

Nothing came of the backchannel discussions.

On 17 January 1967 the installation of the last (2,194th) precast shell segment effectively marked completion of Stage Two and work on the interiors could begin.

Stage Three presented a formidable challenge for the architects and engineers involved. It included revisions to the major hall along with the need to find solutions to the interiors across the Opera House. The distinctive design of the foyers fused the design aesthetics of both Utzon’s and Hall. Utzon had envisaged curtains of glass that appeared suspended from the roof shells, supported by discrete plywood and brass mullions. The design and engineering solution developed by Arup’s firm and Peter Hall balances Utzon’s vision with engineering and acoustic considerations, striving to maximise the viewing area and minimise support elements such as the mullions.

Imported from the French company Boussois-Souchon-Neuvesel, more than 6200 square metres of glass was ordered for the project. The design of the enclosing glass walls posed extraordinary technical and architectural problems that were resolved with great ingenuity by Hall and his talented team. They were recognised internationally at the time as yet another extraordinary achievement that brought to life a key Utzon design premise: that the foyers must have an implicit visual relationship with the harbour surrounding them.

One of Hall’s finest achievements – and most significant challenges – was the Concert Hall. From the start, he faced pressure from the government and the ABC to better accommodate the needs of the Sydney Symphony Orchestra amid concerns about the suitability of the existing dual-purpose design to adequately cater to a range of symphonic concerts and large-scale operas. The recommendation that it should instead be specifically designed for only symphonic concerts was already gathering momentum by the time Hall began his study tour of Europe and the USA in 1966. He departed with a particular focus on investigating the seating and acoustic elements and returned having garnered the consensus that the dual-purpose design approach was indeed inferior and recommended a single-purpose design catering specifically for symphonic music. The government was quick to agree, and the changes had profound repercussions for the Opera House project as a whole.

Even after the opening of the Opera House in 1973, much commentary continued to downplay Hall and his partners’ achievements in bringing the building to completion. Despite this, in the 1980s, as part of a NSW Government bicentennial project, Hall returned to the Opera House and worked closely in association with the Government Architects Office on the repaving of the Forecourt and creation of the Lower Concourse in line with Utzon’s original design ideals.

In 2006, the Royal Australian Institute of Architects posthumously awarded Hall their 25-year award in recognition of his role in completing the Opera House. In reviewing Hall’s work, the RAIA found the venues to be ‘among the major achievements of Australian architects of the 1960s and 1970s’ and that they combined with Utzon’s ‘great vision and magnificent exterior’ to form ‘one of the world’s great working buildings’.

Art at the House

To step inside the Sydney Opera House is to immerse yourself in a world of wonder and creativity. From the foyers to the glass walls to the paintings and the tapestries, the interiors have been designed and put together in a way that aspires to the promise of the building itself, a living sculpture on Sydney Harbour.

Learn more about art at the House.

Murals

Two years before the opening of the Sydney Opera House, James Gleeson, the artist and chairman of the William Dobell foundation, asked John Olsen to create a mural for the new building. Olsen, one of Australia’s most celebrated painters, accepted the commission with enthusiasm. He cast his eyes to the sea and to poetry, his enduring passion. For his subject, he settled on Five Bells, a 1939 poem by Kenneth Slessor about a man who had drowned in Sydney Harbour, weighed down by bottles of beer in his pockets. Slessor’s elegy ends with a meditation on the water at night:

I looked out of my window in the dark

At waves with diamond quills and combs of light

That arched their mackerel-backs and smacked the sand

In the moon’s drench, that straight enormous glaze,

And ships far off asleep, and Harbour-buoys

Tossing their fireballs wearily each to each,

And tried to hear your voice, but all I heard

Was a boat’s whistle, and the scraping squeal

Of seabirds’ voices far away, and bells,

Five bells. Five bells coldly ringing out.

Five bells.

Olsen’s mural, which took shape nearby in an old wool store in the Rocks, is an effulgence of colour and movement and underwater life. Salute to Five Bells, described by the artist as a “nocturnal mural,” was unveiled in 1973 in the Northern Foyer of the Concert Hall.

In his book 2015 book, My Salute to Five Bells, Olsen explains how one can always find something different to appreciate in his artwork: in addition to the detail, the way it swings east to west into the harbour on a moonlight night. “It’s got a state of grace about it,” he writes. “I really think that I’m separate from it, that it has its own way of life. It is a poetical statement; you’ve got to become part of the harbour to really appreciate it. The mural has a story to tell and it will be reinterpreted by subsequent generations.”

Another much-loved mural, Possum Dreaming, a major piece by the late Warlpiri artist Michael Nelson Jagamara, can be seen in the Northern Foyer of the Joan Sutherland Theatre. Spanning 10m x 1.8m, Possum Dreaming was unveiled in 1988 as part of a Bicentennial commission with Cadbury-Schweppes. It was commissioned to replace a photographic mural that had previously hung in the Northern Foyer since the Opera House’s opening in 1973.

Tapestries

The four tapestries that call the Opera House home reveal fascinating stories about the Opera House’s rich cultural heritage and design legacy.

The tapestries – Le Corbusier’s Les Dés sont Jetés or The Die Is Cast (1960), John Coburn’s Curtain of the Sun and Curtain of the Moon (1973), and Jørn Utzon’s Homage to Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach (2004) – are all strikingly beautiful works of modern art.

The tapestries reflect Danish architect Jørn Utzon’s design intent for the interior of the Opera House, where he envisioned the use of modern art and vibrant colour to heighten audience members’ sense of anticipation as they took their seats. This vision for the building was in part implemented by Peter Hall, who completed the interiors of the Opera House and implemented Utzon’s ideas through his own design lens.